|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

This page continues our story of our ancestors as they learned to live under Roman rule. At the bottom of the page I've saved material I previously wrote about possible family origins amongst the Etruscans & Raetians and the Sarmatians. I've saved these because I did the research back when these possibilities were being much talked about and I don't feel like destroying them after all the work I put in. However, recent tests of ancient DNA have shown that the Etruscans evolved locally in Italy and that Sarmatians were part of haplogroups R1a, R1b and Q1a, not G.

At this point I'll continue with the idea that our family was part of some indigenous British population who arrived on the island sometime in the BCs. Perhaps they were descendants of the Bell Beakers with an overlay of Celtic culture; the jury is still out. They would soon be overwhelmed by the Romans and quickly become Romanized, if only thinly.

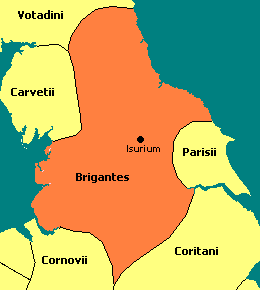

While Julius Caesar famously invaded Britain in 55 and 54 BC, the conquest of the island did not begin until 43 AD under the Emperor Claudius. His general, Aulus Plautius, confronted a variety of Celtic tribes with four Roman legions and, by 47 AD, most of southeastern Britain had been overrun. The next step was to conquer the north, which was dominated by a Celtic tribe known as the Brigante. By the way, what the exact relationship was between the Brigantes of Britain and the Brigantii of Raetia is unclear.

"Several classical writers note that there were Celtic tribes whose territories were found in both the continent and Britain, such as the Belgae or the Parisii; it is possible that the Brigantes were a contingent of Brigantii that moved into Britain around the same time the Belgae did so." - from Ancienttexts.org

While punitive expeditions had been made before, the first concerted Roman effort against the north began during the governorship of Quintus Petillius Cerialis, circa 71 AD. This does not appear to have been an attempt at conquest, but simply a more vigourous and thorough attempt to punish the Brigante for their unruly behavior.

While punitive expeditions had been made before, the first concerted Roman effort against the north began during the governorship of Quintus Petillius Cerialis, circa 71 AD. This does not appear to have been an attempt at conquest, but simply a more vigourous and thorough attempt to punish the Brigante for their unruly behavior.

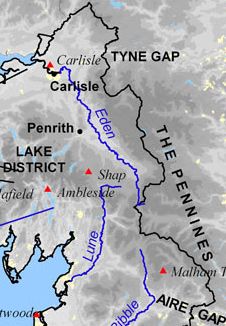

The Romans made a two pronged attack on the north. For the attack on the western domains of the Brigante, along Morecombe Bay, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, commander of Legion XX Valeria Victrix at Wroxeter, established a base of operations at Chester, Deva, where there was already an auxiliary fort built, guarding the river Dee estuary. He moved his Legion north, proceeding through Middlewich and crossing the Mersey river near Wilderspool. He then crossed the Ribble near Walton-le-Dale, heading towards what is today Lancaster. From there the Romans most likely followed the line of the Lune river.

Legion IX Hispana out of Lincoln, Lindum, under the command of governor Quintus Petilius Cerealis, took a parallel course through the eastern provinces of the Brigante and those of the Parisii. He crossed the Humber estuary, probably at Brough, Petuaria, and, at about two days further march north, established a fortress on a well-positioned site between two rivers. It was given the name Eboracum, now York. In time York would become the capital of northern Britain.

Legion IX Hispana out of Lincoln, Lindum, under the command of governor Quintus Petilius Cerealis, took a parallel course through the eastern provinces of the Brigante and those of the Parisii. He crossed the Humber estuary, probably at Brough, Petuaria, and, at about two days further march north, established a fortress on a well-positioned site between two rivers. It was given the name Eboracum, now York. In time York would become the capital of northern Britain.

The two armies joined for the descent on Carlisle, Luguvalium, in the lands of the Carvetii. The northern resistance was broken and the area remained sufficiently safe to allow the resumption of campaigning in Wales in the mid-70's. - taken from The Early Years of Roman Occupation at Lancaster by David Shotter.

Agricola was made governor of Britannia in 78 AD and in the following year began the actual conquest of northern Britain. As Agricola's army pushed north along the Lancashire shore, a Roman fort was built at Lancaster, Calunium, on a hill commanding a crossing over the river Lune, just east of the present-day village of Heysham. This fortification was built of timber, surronded by a clay and turf rampart.

Conquest of the north, including the Scottish lowlands, was completed by 84 AD. Later the Romans would pull back to a line marked by Hadrian's Wall.

In Trajan's reign [c102 AD] the fortress at Lancaster was rebuilt in stone. It survived into the early 5th century. Today lines of Roman ramparts from the old fort can still be seen (just barely) in Lancaster at the Wery Wall, pictured to the right, off Vicarage lane. The fortress at York was rebuilt in stone in 108 AD. Portions of the original wall and one tower are still visible today.

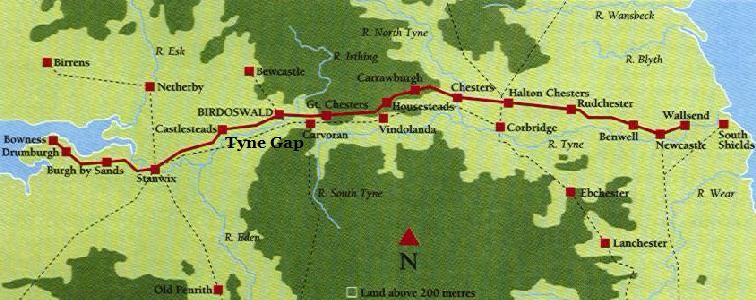

| Historical Timeline: Britannia, Hadrian's Wall

A lesser fortification, known as the Antonine Wall, was built further north in the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius, the adoptive heir of Hadrian. It was built across central Scotland from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde, and marked the furthest extension of rule by the Romans. It consisted of a line of forts connected by a dirt rampart, built on a stone base, and a ditch, or moat. It was manned from about 142 to 164 AD, and again briefly from 208 to about 211 AD, when the legions marched south, abandoning Scotland. |

One garrison unit at Calunium whose name was recorded was the Ala Gallorum Sebosiana, the Wing of Sebusian Gauls, a cavalry unit commanded by Octavius Sabinus. This was during the period when Britannia was part of the break-away Gallic Empire, from 260 to 273, during the Roman Empire's Crisis of the Third Century. The Sebusian were Gauls from the Loire valley of today's France. There was also a unit of bargemen, the Numerus Barcariorum, essentially Marines.

Outside the fort were governmental buildings and a bath house. The local population settled around the fort, trading with the soldiers and providing services. A large number of Roman coins have been recovered from the site.

Five Roman altar stones have been recovered from Lancaster. Of those that are decipherable, two were dedicated to Mars or Mars Cocidius, a conflation of the classical god and a popular Germanic god of war, and one to the Celtic river-god Ialanus.

No Roman remains have been found in the village of Heysham itself.

Everyday Life in Roman Britain

Town life was a social revolution for the largely rural Celtic society. The Romans encouraged the growth of towns and saw urban life as the epitome of sophisticated civilization. These towns became vibrant centers of commercial activity and trade flourished. The Romans built their towns in lowland areas, such as fords across rivers, in contrast to the earlier Celtic practice of sticking to the slopes and higher ground above the valleys. Towns also tended to grow up around army bases. A complex series of roads, built to exacting Roman standards, linked these towns and fortresses in an effective commercial and military web.

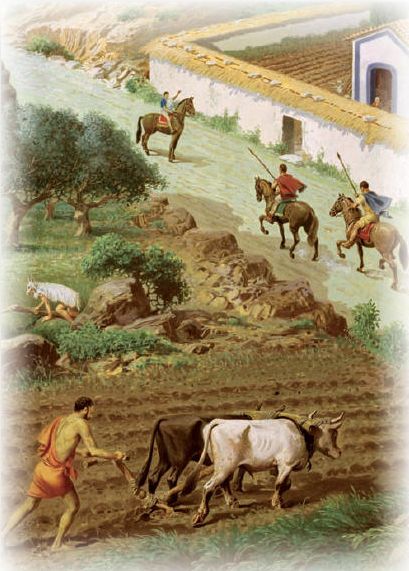

In the countryside a "villa" system was introduced. These were the country estates of wealthy Romanized Celts, built usually within 10 miles of a city center. Villas were focused on the "great house," much like a plantation of the American ante-bellum south, and were centers of rural industry and agriculture. This system was most extensively instituted in the southeast.

Slavery was integral to the Roman Empire and the slaves gathered in war from its rapid expansion funded an opulent life style in the city of Rome. The Villa's of Britannia would have been worked by Celtic slaves. The islands of Britain and Ireland also provided slaves for export to the rest of the Empire.

Britain was a valuable province and through most of its history it was protected, and subdued, by three legions. In the north was Legion IX Hispana, based was at York, Eburacum. In about 120 AD they were replaced by Legion VI Victrix, the Victorious Sixth, who remained until circa 400. The latter built Hadrian's Wall. There was also a large legionary base at Chester.

At its height, the population of Roman Britain was almost 5 million.

| Religion

The Celts had been Druids and, as a center of rebellion, this religion had been vigorously suppressed. The Romans brought with them a variety of religions including the traditional Greco-Roman gods, the compulsory worship of the emperor as a god, the popular rites of Isis from Egypt, as well as many eastern religions that were favored by the Legions. Later, under the Emperor Constantine, who had been born in York, Christianity became the state religion. |

The only classical geographical treatise that deals with Britain's northwest coast is Ptolemy's Geographia that was published in the latter half of the second century. In this work Claudius Ptolemaius describes the ancient British coastline, naming the Moricambe Aestuarium (Morcambe Bay). Morcambe is Celtic for "curved inlet" and appears to have been applied to the river Lune as well by the natives. Ptolemy also mentioned the Setantii as a sub-tribe of the Brigantii. Official correspondence of the Roman military commander in the north in 81 AD also mentioned these local tribes.

This culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, a people of Celtic language and custom.

Thousands of Roman businessmen and officials and their families settled in Britannia. Roman troops from across the Empire, as far as Spain, Syria, Egypt, and the Germanic provinces of Batavia and Frisia, were garrisoned in Roman towns, and many married local Britons. The Roman army and their families and dependents amounted to 125,000 people out of Britannia's total population of 3.6 million at the end of the fourth century. There were also many migrants of other professions such as sculptors from Roman Syria and doctors from the Eastern Mediterranean region. This diversified Britannia's cultures and religions, while the populace remained mainly Celtic, with a Roman way of life.

The affect of Romanization, however, would be felt most keenly in the south of Britain, where the Roman presence was greatest, and wherever large concentraions of Roman troops were found. In the north, in rural districts, there would be little interaction between Britons and off-islanders.

In the post-Roman period the more Romanized population clung to Roman ways and laws. However, disparate interests tore the population apart as Picts from the north and Anglo-Saxons from the east fought for control.

The fortress at York soon spawned a town, or vicus, on the west side of the Ouse river, where the cemetery and, probably, the yet-to-be-discovered amphitheatre were also situated. The beheaded skeletons of gladiators were discovered nearby in 2004. York became the capital of Britannia Secunda, which encompassed all the land north of the Humber and south of Hadrian's Wall.

"In Roman times—which for Yorkshire began about A.D. 70 and ended in the early fifth century—the geography of northern England was different from that of today. Much of the Vale of York was marshy and impassable. Travel across it was only possible by using the ridges of higher ground, the moraines left by the glaciers of the last Ice Age. The Vale of Pickering was still unreclaimed from the lingering traces of the great lake which had occupied it in glacial times, and there were great stretches of swamp in the Humber Fens. In places there were thick forests, of which little today remains, except for place names on the map; for example, the Forest of Galtres, near York; the Forest of Elmet, near Leeds, and Knaresborough Forest. Even the configuration of the coastline was different.

T=Tadcaster, Y=York, S=Stamford Bridge, B=BroughThe Romans came to this wild and inhospitable area in order to provide a defensive bulwark with which to protect the settlements in the lowlands of eastern and southern England. They found it necessary to subdue the Celtic-speaking Brigantes in Yorkshire, and to hold at bay the warlike Picts and Scots further north. The Roman occupation of England began in earnest in A.D. 43, but it was almost thirty years later before they crossed the Humber and advanced into Yorkshire. One of the main routes along which they advanced was from Lindum (Lincoln), along the chalk Wolds to the Humber, to the west of the site of the present Humber Bridge.

There may have been a ford—and there was certainly a ferry—across the Humber, which enabled them to cross to their landing place at Petuaria (Brough),: where many early Roman coins and pottery fragments have been found, as well: as a few traces of their settlement. From Brough the Roman route ran under the scalp of the Yorkshire Wolds, eventually crossing the Derwent valley and the Vale of York to reach the present site of York. A branch road passed through Delgovicia (near Millington) and over the Wolds to Derventio (Malton), which became an important route centre on the road between York and the coast at Scarborough and Filey, where Roman signal beacons were erected to guide coastal shipping. The main trunk road up the Vale of York, linking the settlements of Danum (Doncaster), Calcaria (Tadcaster), Isurium Brigantium (Aldborough) and Cataractonium (Catterick) is followed in part by the modem A1. For much of the way it runs along a line of low magnesian limestone, which not only afforded a dry and relatively open route, but was also a source of excellent building stone. The map of Roman roads shows that in the main they followed upland areas: the chalk Wolds, the Pennines and the North York Moors. Apart from the fact that these lines of communication were easier to build on, because there was no need to clear forests or to drain marshes in order to make the roads, they were also easier to defend, as the open vistas of the hills gave warning of the approach of enemy forces."

Roman Roads in Yorkshire and Lancashire

The map above shows how Roman roads, built between the 1st and 5th centuries AD and surving into the 16th, improved the ease and speed of movement around Britain. Our family could have moved either west to Lancaster, or east to York via good Roman roads which, in the day, would have also have been supplied with way-stations providing food and shelter. By the way, the road from Doncaster to York was known as Ermine Street.

Just north of York was Isurium Brigantium, Aldborough. Although only a small village today, it was the second largest military settlement in the area. The road that runs next to it connected York with forts right up to the Antonine Wall in Scotland, while another road branched off from it to Luguvalium, Carlisle.

The Parisi were, then, more Romanized than other Celts in the north."Once they had penetrated into the Pennines, the Romans soon discovered the valuable deposits of lead ore and, within a few years of the defeat of the Brigantes at Stanwick in A.D. 74, they were smelting lead at Greenhow, above Nidderdale. Tacitus, Agricola’s son-in-law, records that Brigantian prisoners taken at Stanwick were set to work mining lead and building roads to the lead mining areas. Two pigs of lead, weighing over 155 lbs. each, have been found near Greenhow and are stamped with the inscription IMP. CAES. DOMITIANO AVG, COS. VII (Imperatore Caesare Domitiane Auguste Consule Septimum) which indicates that they were cast in the seventh term of office as consul of the Emperor Domitian—i.e. in A.D. 81. One of these pigs can be seen in the British Museum and another in Ripley Castle. A third pig, now lost, was inscribed with the name of the Emperor Trajan, who ruled between A.D. 91 and A.D. 117. The Romans used lead for water pipes and as an alloy with tin in the manufacture of pewter ware. They are also known to have worked the iron ore deposits in the coal measures in the Bradford and Sheffield areas.

Although there were economic benefits which could be derived from the occupation of Yorkshire and the exploitation of its timber and mineral resources, the primary reason for the Roman presence was military. By A.D. 77, when the Emperor Vespasian appointed Agricola as governor of Britain, Eboracum (York) had become the headquarters of the famous IX Legion, and most of the Roman settlements were military stations, like Olicana (Ilkley), Castleshaw, Slack, Cataractonium (Catterick) and many temporary Roman camps, like those at Cawthorn and Goathland on the North York moors. During the second century, however, with the completion of Hadrian’s Wall, the military threat lessened; and some civil settlements grew up. The largest of these was at Isurium Brigantium (Aldborough). There was also a large civil settlement at York, and another near Boroughbridge and there were a number of villas (country houses) in East Yorkshire. The best known of these was at Rudston, near Bridlington, and there are some outstanding Roman mosaics from villas in the Humberside area to be seen in the Hull Museum. The relations between the Romans and the Parisii, who lived in Holderness and on the Wolds, were better than those with the Brigantes and a merging of the Roman and Celtic cultures occurred. This may help to explain the greater frequency of non-military Roman settlements in East Yorkshire.

"There is little to be seen, except their magnificent sites, of the line of signal stations which were built along the North Yorkshire coast. Typical of these is the one at Goldsborough, which stands on the highest point above Lythe Bank, and guards the approach to Whitby. It commands a view over the North Sea which would give watchers there ample warning of the approach of shipping, and a beacon lit at this point could be seen for many miles out to sea. Another signal station was located on Castle Hill, Scarborough.

The Romans have not left us many place-names—Catterick, derived from Cataractonium is an obvious one—but their most abiding legacy in Yorkshire is the road system which the invaders left behind. Although they occasionally sited their roads along the lines of older British tracks, many of them struck out along new routes. It may be an exaggeration to say, as the Duke of Edinburgh once did, that until the motorway building of the post-war period, no new roadways had been planned in Britain since the Romans left; it is undoubtedly true that, until recently, much of our national road system followed the lines established by the Romans. Mention has already been made of the relationship between the Al and the Roman road along the Vale of York. Other modern main roads which follow the routes of Roman roads are the A166, from Stamford Bridge to Driffield; the A1079, between York and Market Weighton; the A59, between Blubberhouses and Harrogate and between Green Hammerton and York; and the A1034, between South Cave and Market Weighton. There are also some stretches of the original Roman routes which can be seen, as on the moors above Goathland, and on Blubberhouses Moor. The road across Blackstone Edge may also be a Roman road, although this is not certain. It is not always possible to tell which parts of these surviving roads have been improved and repaired during the later centuries.

In A.D. 402 the Roman garrison was recalled from York by Stillicho, the regent of Emperor Honorius, who was himself of Vandal origin, because of the desperate situation in Rome and, although some vestige of Roman influence remained for a few more years, Yorkshire passed along with much of the rest of Europe into the Dark Ages." - from Roman Yorkshire

As pointed out above, due to better relations, there was a greater frequency of non-military Roman settlements in East Yorkshire.

"But what of that other Yorkshire tribe, the cart-driving Parisi? It seems that they were friendly with the Romans from the beginning and so their immediate fate was rather different to that of the Brigantes. It is likely that their territory provided safe passage for Roman troops during the first phases of the conquest of the Brigantes (who were tribal rivals). If so, the Romans were suitably grateful, for there is no evidence of any violence in the capitol, Petuaria (Brough) and the area seems to have gone its own way and prospered quietly as the Parisi too came under Roman rule.

Life for ordinary farming people in Roman Yorkshire was far less influenced by the occupation than further south, where large slave-run farms provided huge amounts of grain for the army. Field systems remained much the same as before and the traditional round houses, some of them hundreds of years old, remained in use. A few villas were built, notably those at Rudston and Langton, but there is curiously little evidence that typical Roman goods like glass, kitchen ware and amphorae of wine found their way down to ordinary people. Even the mosaic floors that survive are merely crude country versions of the more splendid ones in southern villas." - from "The Romans in Yorkshire"

| Rudston, East Yorkshire

|

| Historical Timeline: The Roman Withdrawal

Roman control of Britain began its slide with the revolt of Magnus Maximus, the local military commander, who declared himself Emperor in 383 AD. He stripped the island of troops to fight his continental battles with the Western Emperor, Gratian. Though he defeated Gratian, he was in turn overthrown by Theodosius in 388. Then, in 407, the Emperor Honorius began to officially recall the Legions. Attacks on the Roman frontiers by the Visigoths from eastern Europe meant that reinforcements were desperately needed elsewhere and the Romans could no longer hold on to Britain as a military province. In the North of Britain, the depletion of the Roman army left the northern frontier of Hadrian's Wall severely exposed and revolts against the small scattering of Romans who remained soon gained momentum. In 410 the Roman citizens of Britain appealed to the Emperor Honorius for help, but with the Goths ravaging Italy he was in no position to aid them. He famously replied that they must "look to their own defences." |

When the empire finally withdrew, it withdrew its payroll as well and the villages that supported the old forts at Great Chesters and Carrawburgh collapsed.

When the empire finally withdrew, it withdrew its payroll as well and the villages that supported the old forts at Great Chesters and Carrawburgh collapsed.

The Roman withdrawl left a power vacuum in which various Celtic kingdoms arose, attempting to impose order and extend their own influence. In the north, on the western slopes of the Pennine mountains, was the kingdom of Rheged, with its capital in Carlisle. On the the eastern side of the mountains was Bernicia. Early on the latter kingdom was conquered by the Angles and, circa 600, they were moving west, through the Tyne Gap, to dominate Rheged, and later conquer them. This conflict gave further impetus to southward migration.

By medieval times this remote region along the wall had reverted to waste and woodland.

Our ancestors, in the face of increasing unrest and economic distress, would have moved west, from the region near Great Chesters, down the Irthing river, then south, away from the dangers of the border and toward the more fertile lands of the Eden river valley. There were excellent Roman roads leading south. The high road, along the Northern Pennines, was the Maiden Way, leading south from Carvoran, Magnis Carvetiorum, just west of Great Chesters. The low road went through the Eden river valley, coming out of Stanwix, Uxelodunum, just north of Carlisle. The distance was not great, and the intervening mountains not very high, down to the Lune river valley of Lancashire and the village of Heysham, in the new kingdom of South Rheged, a sub-realm ruled by cousins of the kings in Carlisle. However, there was almost a thousand years from the collapse of Roman rule to the appearance of the Hessam surname in Lancashire, so they could have taken their time. In that intervening period occurred the Anglo-Saxon conquest, the invasion of the Vikings, and incessant raids out of Scotland to keep the people moving south.

The movement of haplogroup G may have been more indirect than the latter scenario suggests. As will be discussed on later pages, they may have come into northwestern France during the late Empire or early Middle-Ages, then into England during and after the Conquest. This, of course, helps preserve the Gernet-Heysham connection which will be discussed later.

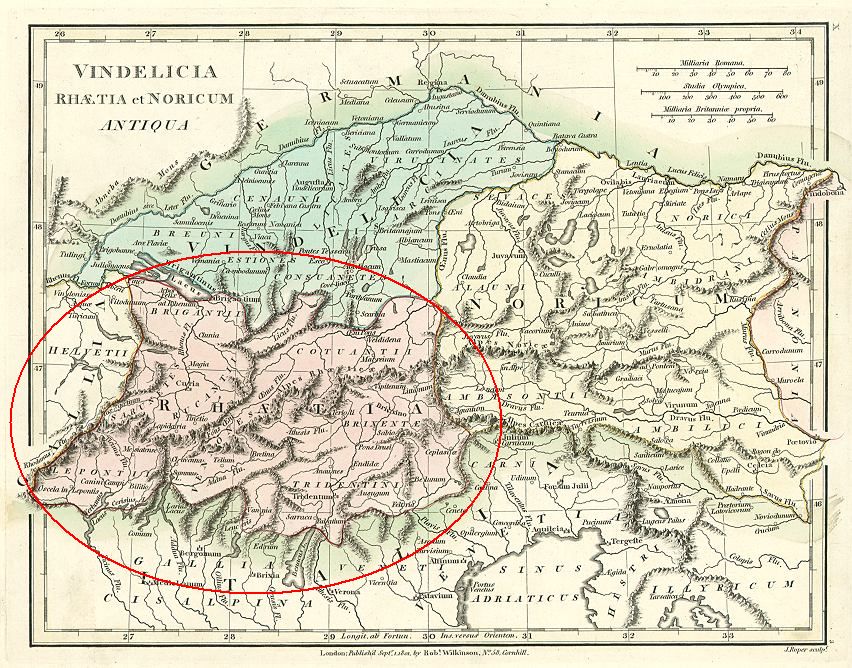

The distribution of the G2a-L497 mutation in Switzerland and the Austrian & Italian Tyrol corresponds rather neatly to the old Roman Alpine province of Raetia. Its native inhabitants were, according to the Roman historian Livy, descendents of the Etruscans. The Etruscans called themselves Rasenna, which may be indicative.

"The latest theory that has the most interest involves the Raetians of eastern Switzerland. Although scholars are divided over this issue, some think the Raetians are a type of Etruscans. The Etruscans are thought to have come to northern Italy from the Near East, and they definitely arrived there before the establishment of the Roman Empire. The Raetians were added to the Romans' empire soon after its establishment, and they were known for eager enlistments as Roman auxiliaries. Two of the major locations to which they were sent were Britannica [England] and southwestern Germany, the areas where men unusually closely related to these Swiss [L497] men are located today. It is to be noted that in Britain and Germany that the [L497] men closely related to Swiss men also have other Swiss as their most distant [L497] matches, indicating a G mixture among the Swiss over a prolonged period. In addition, those Swiss nearest to Brits and Germans include a variety of Swiss [L497] men -- not just the same men." - Ray BanksAs recorded by Roman historians, the Etruscans, and the Raetians after them, spoke an archaic language that seems to have predated the Indo-European languages brought into Europe by the R1a/b invaders of the Bronze Age. That is, the Etruscans, like the Basque, are likely a vestige of the Neolithic culture, dominated by haplogroup G2a, that was otherwise swept away. The last person known to have been able to read Etruscan was the Roman emperor Claudius.

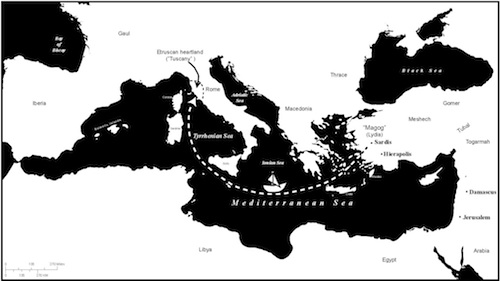

The Etruscans, a sea-faring people, inhabited a land called Etruria, today's Tuscany, just north of the nascent city of Rome. In addition to farming, they had numerous mines of lead, zinc, copper, silver, and iron, and a good trade in the western Mediterranean. As their power grew they expanded south into Latium and Campania, north into the plains along the river Po, and into the island of Corsica. How they came to live in Etruria was, even in Roman times, the stuff of myth and legend.

| The Origin of the Etruscans

If they were indigineous, the Etruscans were heir to the Villanovan culture, 1100-700 BC. The latter were an Iron Age culture of central and northern Italy which branched off from the Urnfield culture of central Europe. During the 7th century an orientalizing culture, introduced by the Greeks, was superimposed on the Villanovan in Tuscany. The northern Villanovans of the Po valley, however, continued to produce art of the previous style as late as the last quarter of the 6th century when Etruscan expansion obliterated their culture. At their maximum, circa 650 B.C., the Etruscans ruled the city of Rome, but they were penned in by the expansionist Greeks of southern Italy and Sicily, and by the Carthagians in north Africa and Sardinia. Successive defeats at the hands of the Greeks, an invasion out of the north by the Gauls, and revolts by their subjects in Campania, weakened the kingdom. Finally a newly vigorous Rome conquered the Etruscans in the 3rd century B.C. |

The first account of the origins of the Etruscans was provided by the Greek historian, Herodotus, in the 5th century BC. He wrote that they came from Lydia, in Asia Minor.

| Lydia

After the demise of the Hittite Empire a new kingdom of Lydia was founded, encompassaing most of western Turkey. |

| The Origin of the Etruscans, cont.

According to Herodotus, due to a famine in Lydia many emigrated west, to Smyrna on the Aegean coast, built ships and put to sea to find a new home.

|

A modern theory I'm more comfortable with uses the disorders of the 12th century B.C. (and famine?) as the motive force for this migration. The Hittite empire, which occupied the central plain of Asia Minor, east of Lydia, also collapsed at the same time.

| The Collapse of Empires

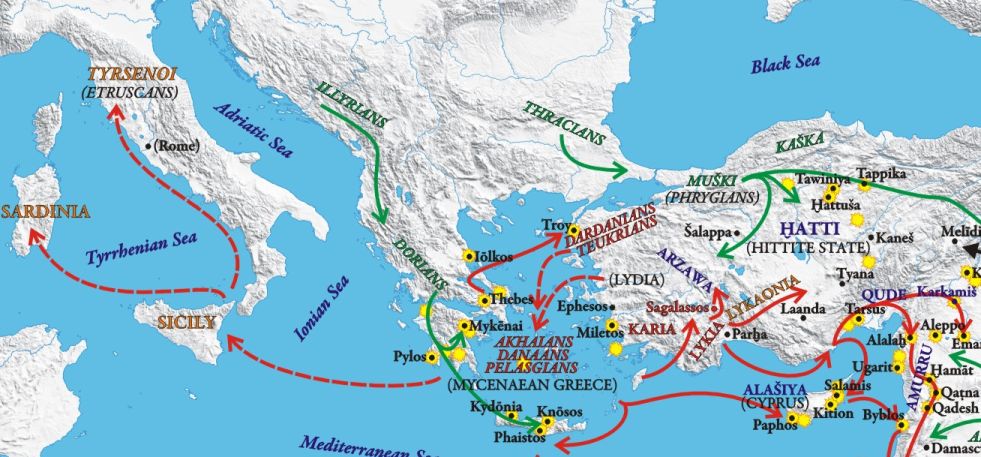

In the early 12th century BC large populations were in motion, perhaps driven by drought and famine, but looking for new lands. They fell on the Egyptian and Hittite empires, destroying the latter and greatly weakening the former. Those coming out of the Balkans included the Illyrians, Thracians, Dorians and Phrygians. The Dorians destroyed the Mycenaean civilization of early Greece and Crete, then went on to found many classic Greek cities, such as Corinth and Sparta. The victim population, the Ionians, were either made slaves, like the Helots of Sparta, or sheltered in defensible places, like the Acropolis of Athens. Note that the ancient Greeks thought that the Trojan War was an historical event that had taken place in the 13th or 12th century BC (Eratosthenes, born 276 BC, dated them as 1194-1184 BC). Perhaps this epic was an echo of the conflict and chaos of those times. "After centuries of brilliance, the civilized world of the Bronze Age came to an abrupt and cataclysmic end. Kingdoms fell like dominoes over the course of just a few decades. No more Minoans or Mycenaeans. No more Trojans, Hittites, or Babylonians. The thriving economy and cultures of the late second millennium B.C., which had stretched from Greece to Egypt and Mesopotamia, suddenly ceased to exist, along with writing systems, technology, and monumental architecture." - from a comment on the book "1177; The Year Civilization Collapsed" by Eric H. ClineTroy was discovered in the 19th century by Heinrich Schliemann near the Dardanelles, just north of Lydia.  |

The proto-Etruscans may have been forced out of their homeland in western Turkey by the marauding Phrygians and other populations uprooted in the chaos. The kingdom of Lydia, as the Greeks knew it, arose in the aftermath of the Hittite Empire's fall.

| The Origin of the Etruscans, cont.

Hellanicus of Lesbos, however, wrote that the Etruscans were an offshoot of the Pelasgians who had inhabited Thessaly, in central Greece, before coming to Italy. In the G haplogroup map note the concentration of G-type in Thessaly. Thucydides, writing of a campaign in the Peloponnesian War, characterized the people of the Chalicidic Peninsula, that odd three-fingered penisula in the upper Aegean, just west of Lemnos, as "Tyrrheno-Pelasgians once settled in Lemnos and Athens." The term Pelasgians should probably be understood here as a catch-all term for any pre-Greek people in the Aegean. Homer listed them as allies of Troy.

Roman authors also felt the Etruscans had an eastern origin and this story, I think, informs the later Roman legend of Aeneas of Troy, as the founder of Rome. The Romans copied much from the Etruscans, including, I think, their foundation legend. Remember that Aeneas, a son of King Priam of Troy, took a remnant population of the city after its defeat by the Greeks, sailed west from Asia Minor, right, and, after a few dalliances mimicing Odysseus, founded the city of Rome. Of note, the Etruscan's earliest history dated back to 969 BC when the first period of their calendar [saecula] began, per Varro, as cited by Censorinus in his De die natali of 258 CE. This may align with the establishment of their new homeland in Italy, after a period of wandering following their departure from Asia Minor. This origin theory does not presuppose that all Etruscans came from Asia Minor. A more likely scenario is that a small number of Middle-Eastern settlers, technologically and militarily superior to the natives, conquered the region. Then, over time, the conquered people adopted the culture, language and identity of their overlords. The genetic origin of the people who became known as Etruscans would then have been composed predominantly of the aboriginal population with perhaps 10% of foreign origin. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA in Tuscany found eleven lineages not found elsewhere in Europe, but which do occur in the Near East. Apparently even the cattle and goats of this region bear an eastern origin. Note, this was said in the New York Times, so it must be true! Below are images of Etruscans taken from tomb murals. Hey, that looks just like Aunt Alice!  |

Justin and Pliny the Elder reported that a portion of the Etruscan people who had settled in the plains of the Po river had, in the declining years of the Etruscan Empire in the 4th century BC, been driven north, into the Alps, by invading Gauls. This alpine region became known as Raetia. The modern historians, Niebuhr and Mommsen, agreed.

| Etruscan Language

The language of the Etruscans was unique. It was not an Indo-European type, like those of the rest of Europe, and it is not related to any living language. A relationship has been suggested between Etruscan, Raetic, and Lemnian, that of the island of Lemnos, as a Tyrsenian language family. Each of these demonstrates close connections in vocabulary and grammar. Others in this group may include the extinct Hattili language of central Anatolia. An amateur researcher writes, Before the Indo Europan invasions the most common (and the first known) language of Anatolia [Turkey] was Hattili until the Hittites came to the same area. Hattic civilisation was so settled that even Hittites themselves named their country as "land of the Hattis." In the following centuries Hattili survived only in Hittite prayers and ceromonies, names of places etc. Most of the linguistic evidence suggests a correlation between Hattili and North-west and South-west Caucasian languages (both Georgian and Circassian groups). Considering that some ancient languages, such as Caskian, are related to Hattili, we might assume that most of the Anatolia was part of the Caucassian languages block. Some scholers assumed a similar correlation between the Tyrsenian family - which includesd Etruscan and Caucassian languages - although this relation is not as clear as the Hattili sample, and most linguists tend to classify Tyrsenian as a language isolate." - by Turkmen*Of interest to this theory, a Y-DNA sample taken from the island of Lemnos, in the Aegean Sea, due west of ancient Troy, was type-G with the L497 mutation, as was a sample from the west coast of Turkey. The language of Lemnos is accepted as being closely related to Etruscan. Its writing system used an alphabet similar to that seen in the Etruscan and older Phrygian languages, both derived from the alphabets of Anatolia. |

The counter theory is the obverse of the above; that the Raetians and the Etruscans were indiginous descendents of Neolithic haplogroup G2a-L497 farmers who had moved south into the Alps during the turmoil of the Bronze Age invasions. Later, circa 1100 BC perhaps, some of them crossed the mountains into the Po river valley and then on into modern Tuscany. There they established the Villanovan culture which later evolved into the Etruscan kingdom. Etruscan elements in the island of Lemnos would be a result of eastward migration or perhaps simply a trade visit. Note that Greek rulers of the Bronze Age, 1600-1100 BC, recruited groups of mercenaries from Sicily, Sardinia and various parts of the Italian peninsula, which may have included Etruscans/Raetians.

| The Terramare Culture

A Bronze Age culture centered on the Po river valley. Around 1150 BC, at a time when many empires in the eastern Mediterranean were collapsing, the Terramare were completely abandoned, with no settlements replacing them. It has been suggested that the memory of the fate of the Terramare culture may have lasted for centuries, until it was recorded by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, in his first book on the Roman Antiquities, as the fate of the Pelasgians. In his record the Pelasgians occupied the Po Valley up to two generations before the Trojan War, but were forced, by a series of famines of which they could not understand the reason, or find a solution, to leave their once-fertile land and move to the south, where they merged with the Aborigines. - from Wikipedia. The Villanova Culture The earliest Iron Age culture of central and northern Italy, 1100-700 BC. Burial characteristics relate the Villanovan culture to the Central European Urnfield culture and subsequent Celtic Hallstatt culture. It abruptly followed the Bronze Age Terramare culture. During the 7th century an orientalizing culture, introduced by the Greeks, was superimposed on the Villanovan in Tuscany. This was followed without a severe break by the Etruscan civilization. The northern Villanovans of the Po valley, however, continued to produce a geometric art of the previous style as late as the last quarter of the 6th century when Etruscan expansion obliterated their culture. |

Returning to the Alpine tribes, the Raeti inhabited the eastern cantons of present day Switzerland and the greater part of the Tyrol, both of Austria and Italy. They were recorded by Polybius as early as 146 B.C., who simply said they controlled certain mountain passes. According to Pliny they were divided into many tribes, including the Lepontii, Tridentini, Genauni, Vennones, Brixentes and the Brenni. They were subjugated by Tiberius and Drusus in 15 B.C., during the reign of Augustus, and quickly became loyal subjects of the empire, contributing disproportionate numbers of recruits to the imperial Roman army's auxiliary corps - from Wikipedia.

Tribes of Raetia

Also as Rhaetia. The Raeti were a confederation of alpine tribes whose original ethnicity is unknown. If we accept the theory that Etruscans moved into Raetia after being pushed out of the Po valley by the Gauls, it is still probable that they mixed with an indigenous people already living in the mountain valleys. By the time of the reign of Augustus Celtic tribes had moved into the area imposing their culture and language. "Rhaetia. This country, which is now comprised in that of the Grisons [the easternmost canton of Switzerland], of the Tyrol, and in part of Italy, was bounded by the Helvetii on the west; by Vindelicia on the north; by the Alps on the south; and by Noricum and Carniola on the east. It was involved in the conquest of Vindelicia by Drusus and contained the towns of Curia (Coire); Tridentum (Trent); Belunum (Belluno); and Feltria (Feltre); the Brigantii, Lepontii, Rucantii, Cotuantii, Tridentini, Brixente, and Vennones, being among its principal states." - from the "Classical Manual" Raetian language inscriptions have been found almost exclusively in northeastern Italy: South Tyrol, Trentino, and the Veneto region. None have been found in Switzerland, the other core Raeti region. The Raetic inscriptions indicate that Raetian survived as late as the 3rd century AD, suggesting that the Raeti tribes in this region at least may not have converted to Celtic speech. In addition, the abundance of Celtic toponyms and the complete absence of Etruscan place names in the Raetian territory leads to the conclusion that by the time of Roman conquest the Raetians were completely Celticized. BrigantiiCeltic tribe mentioned by both Strabo and Pliny the Elder as living in Raetia. They lived on the shore of the Lacus Brigantinus (Lake Constance). Their capitol was Brigantion, now Bregenz, Austria SarunetesRucantii / Rhucantii Strabo identified them as Raeti, and amongst the boldest of that nation. They lived near the sources of the Rhine. LepontiiStrabo identified them as Raeti and Pliny as Celtic. A Celtic people, their territory included the southern slopes of the Aps, including the St. Gotthard Pass and Simplon Pass, corresponding roughly to present-day Ossola and Ticino. These included the lakes Verbanus (Maggiore) and Larius (Como). The area to the south, including what was to become the capital Mediolanum (modern Milan), was Etruscan around 600-500 BC, when the Lepontii began writing tombstone inscriptions in their alphabet, Lugano, one of five main Northern Italic alphabets derived from the Etruscan alphabet. The Alpes Lepontiae mountain range separates the Lepontii of Raetia from Hevletia. VennonesIdentified by Pliny as Raeti. They lived in the Valteline and extended also to the valley of the OEnus (Inn). CotuantiiStrabo identified them as Raeti, and amongst the boldest of that nation. The Alpes Rhaeticae (Tridentinae) is the range separating the Cotuantii from the Brixentii. They lived down the Inn river. Brixenetae / BrixentesTo the north of the Tridentium, in the Adige river valley. TridentiniThey lived on the river Athesis (Adige). Their city was Tridentium (Trent). CamunniStrabo identified them as Raeti. Pliny classifed them as an Euganean tribe. |

So, to recap, the earliest ancestor of our family was a man who was born in northeastern Africa, say in Kenya, about 200,000 years ago. He was the single progenitor of all of mankind. Some of his descendents, our forefathers, wandered out of Africa, following game, and settled in the Middle East about 50,000 years ago. Of those settlers one was born about 46,000 years ago in the region just below the Caucasus, in eastern Turkey or western Iran, with the anomoly that defines haplogroup G. Our ancestors in this group later drifted west, into the central Anatolian plain, where they became early farmers.

Around 1,200 BC, in the turmoil that resulted from the invasion of the Sea People, the collapse of the Hittite Empire, and, if you believe Homer, the destruction of Troy, our ancestors escaped west, taking to the sea. They eventually settled in northern Italy where they became part of the people known as the Etruscans.

Our ancestors then moved north, to live in the Po river extension of the Etruscan kingdom. In the 3rd century BC the Gauls invaded this region and our forebears were pushed north, into the Italian Alps. This region became known later as Raetia and was subsumed by the Roman Empire at the tail-end of the 1st century BC.

Hmm. Well, it could happen I suppose . . . remember, the fewer the facts the more fanciful the theory.

| Imperial Roman Auxilliaries

The Auxilia, or auxilary troops, were the non-citizen corps of the Imperial Roman army, 30 BC to 284 AD. They served alongside the citizen Legions, received similar training, and provided almost all of the cavalry and the more specialized troops, such as as archers and peltists. They were mostly volunteers, not conscripts, and mainly recruited from the peregrini, free subjects of the provinces who constituted the vast majority of the population in the 1st and 2nd centuries. The Danubian regions, Raetia, Noricum, Pannonia, and Moesia were, with Illyricum, the Empire's most important source of auxiliary recruits. Britain in mid-2nd century contained the largest number of auxiliary regiments in any single province. The Auxilia were organized into regiments the size of cohorts, or about 1/10th the size of a legion. They were of three types, ala, cavalry, cohors peditata, infantry, and cohors equitata, mixed infantry and cavalry. They were led by a praefectus, prefect. Their service, like that of the Legions, was for 25 years, afterwhich they and their children were awarded citizenship. While Auxilia were initially stationed in or near their home provinces, after the Illyrian and Batavian Revolts, they were usually deployed to far regions. Hadrian's Wall, though built by the legions, was garrisoned mainly by auxiliary troops. Many such units remained in their assigned provinces for centuries, with soldiers often retiring within the province where they had served rather than to their original homeland. Over time these ethnically-formed units took on new recruits from their service area, creating situations where native Britons served alongside soldiers from far-flung regions. The army was, then, a great integrating force for the Empire. |

| Training Roman Troops

The Romans were a hard people and their army was renowned for its iron discipline. It is not surprising then that the training of new army recruits was often brutal. Recruits, triones, were provided with 6-months of initial training. The focus of this training was the drill, marching in formation and learning to change that formation and its direction of movement in rapid order. The power of the legion came from its unity and nerveless reaction in combat. They also did a lot of physical exercise, mainly in the form of labor. Failure to perform as requested was met with harsh punishment. Physical training included a 20-mile march in full kit, including two spears, sword, dagger, armor, shield, rations, cooking pot, spade, bed roll, and personal items. This hike had to be completed in under five hours. Weapons practice occurred every morning throughout the soldier's enlistment. For this they used dummy weapons deliberately heavier than the real thing. Of special note was learning how to build a marching camp. When a Roman Army stopped its march for the day they didn't just flop down on the ground and go to sleep. At every stop they built a well-organized and fully defended town, complete with named-streets, a ditch, ramparts and a palisade. Moreover, all Roman campsites looked exactly alike. After this period of training they were promoted to the rank of Gregarius. |

Whether they had an Etruscan origin or not, how did the Raetian men of today's Switzerland and Tyrol, or any of the Alpine tribes, get to Northern England? As Ray Banks indicates above, the Raetians were a warlike people and eager volunteers for the Roman Army. I show several Raetian military units in Roman Imperial employ as Auxiliaries in Germania Superior [the upper Rhine in southern Germany], one in Germania Inferior [on the lower Rhine], and two in Britannia [England]. The latter were Cohors V and VI, in England during the 2nd century AD. A cohort had about 500 soldiers, so we're looking at 1,000 opportunities to introduce a Raetian haplogroup into England's native population.

The Raeti enlisted in the Roman Army in disproportionate numbers. 10 cohorts, or 5,000 men, had been raised by the reign of the Empereor Claudius, and another 2 were raised not long after. This readiness to partake of a life of hard discipline and not inconsiderable risk speaks to the hard life and lack of opportunities the tribesmen found in the Alps.

Two cohorts were stationed in Britannia, at Hadrian's Wall in the far north of England. Another two units, which may have been drawn in part from these cohorts, were also found in this region.

Cohors Quintae Raetorum [The Fifth Cohort of Raeti]

At Carrawburgh, the northern most fort on Hadrian's Wall. This unit was recruited from among the various tribes of the province of Raetia, which comprised parts of western Austria, south-eastern Germany and eastern Switzerland. We know from a military diploma, a brass plate given to a retiring soldier, that the unit was present in Britain in 122 AD. It names 13 cavalry alae and 37 infantry and mixed cohortes - the largest number recorded on any diploma throughout the Roman empire. It is thought that this list represents the entire auxiliary force assigned to the governor Aulus Platorius Nepos, with which he was to garrison the north of Britain while his legionary troops were set to work building the forts, milecastles, turrets and curtain rampart of Hadrian's Wall. Below, auxiliary troops defend a Roman fort from attack.

IMP CAESAR DIVI TRAIANI PARTHICI F DIVI NERVAE NEPOS TRAIANVS HADRIANVS AVGVSTVS PONTIFEX MAXIMVS TRIBVNIC POTESTAT . . .

"Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, son of the divine Trajanus Parthicus, grandson of the divine Nerva, High Priest . . .

For the cavalrymen and foot-soldiers who have served in the thirteen cavalry wings and thirty-seven cohorts which are named

Ala I Pannoniorum Sabiniana

. . .

Cohors V Raetorum

. . .

which are in Britain under Aulus Platorius Nepos. The veteran soldiers who have served twenty-five years and received an honourable discharge from Pompeius Falco, whose names are written below. To them and to their children for posterity has been granted the citizenship. Also lawful marriage to their wives they have at that time they are assigned the citizenship, or, if they were unmarried, with those whom they later marry, provided that it be only one woman for one man. Dated fourteen days before the calends of August in the consulship of Tiberius Julius Capitonius and Lucius Vitrasius Flamininus (17th July AD122)."

- Burn 100; CIL XVI.65; dated: July 17th AD122

The unit was amongst the northern army of governor Aulus Platorius Nepos. Nepos was governor of Germania Inferior and a close friend and possible kinsman of the Emperor Hadrian. He may have accompanied Hadrian on his visit to Britain in 122 AD. In that year he was made governor of Britannia and oversaw the construction of Hadrian's Wall. He probably brought Legion VI Victrix with him from the continent to assist in the construction and perhaps to replace IX Hispana which had left around 108. Nepos' huge expenditure on the frontier work however caused him to fall from Hadrian's favour. He was replaced around 125.

The unit was amongst the northern army of governor Aulus Platorius Nepos. Nepos was governor of Germania Inferior and a close friend and possible kinsman of the Emperor Hadrian. He may have accompanied Hadrian on his visit to Britain in 122 AD. In that year he was made governor of Britannia and oversaw the construction of Hadrian's Wall. He probably brought Legion VI Victrix with him from the continent to assist in the construction and perhaps to replace IX Hispana which had left around 108. Nepos' huge expenditure on the frontier work however caused him to fall from Hadrian's favour. He was replaced around 125.

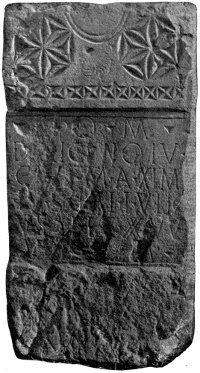

The only inscription evidence found for the unit in Britain is an undatable altarstone to the goddess Coventina, a spirit of wells and springs, at the fort at Carrawburgh, in Northumberland, on Hadrian's Wall.

DEAE COVENTINE P...ANVS MLCHO VRETORVM.... VOTVM LIBES ANIMOR ET POSIVITTheir activities following the Hadrianic period are unknown.

"To the goddess Coventina, P[ublius? ...]anus, a soldier of the Fifth Cohort of Raetians [...] an offering freely and sincerely set up."

- RIB 1529; altarstone

At Great Chesters (Aesica), a fort on Hadrian's Wall. Another unit recruited from among the many tribes of the Roman province of Raetia, among them the powerful Vindelici, the Estiones, the Licates, the Genauni, the Brigantii, the Venones and the Calucones. Aside from the building inscription found at Great Chesters on Hadrian's Wall dated to the latter half of the second century, their escapades in Britain are unknown.

IMP CAESARIBVS ANTONINO ET VERO AVGVSTIS PARTHICIS MEDICIS ARMEN IACIS COH VI RAETORVM ... ...MISIA ..CCI.. ET ... ...IAT...This was early in the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-Empereor, when he ruled with his adoptive brother, Lucius Verus. The emperors are being hailed here for their recent victories against the Parthians [Persians] in Media and Armenia.

"For their emperors, the Caesars Antoninus and Verus, the Augusti of Parthia, Media and Armenia, the Sixth Cohort of Raetians [...]"

- RIB 1737; dated: AD166-169

At Manchester, well south of the wall. A vexillatio was a detachment of a Roman legion or auxilary formed as a temporary task force. It was named from the standard carried by a legionary detachment, a vexillum, which bore the emblem and name of the parent legion. Vexillationes were assembled ad hoc to meet a crisis. They varied in size and composition, but usually consisted of about 1000 infantry and/or 500 cavalry.

...RIC PRAEPOSITVS VEXIL RAETOR ET NORICOR V S L L M

"[...]ric, Commander of the Detachment of Raetians and Noricans, gladly, willingly and deservedly fulfills his vow."

- RIB 576; altarstone

This 3rd century unit is attested at Roxburghshire (Cappuck), Risingham (Habitancium), Birrens (Blatobulgium), and Great Chesters (Aesica). Cappuck and Habitancium were outposts about 3 marching days north of the wall. Blatobulgium was closer, just north of the west end of the wall.

This 3rd century unit is attested at Roxburghshire (Cappuck), Risingham (Habitancium), Birrens (Blatobulgium), and Great Chesters (Aesica). Cappuck and Habitancium were outposts about 3 marching days north of the wall. Blatobulgium was closer, just north of the west end of the wall.

The following altar stone, left, was found in a chamber of a bath building at Great Chesters, a fort on the wall where the Sixth Cohort of Raeti were stationed.

Deae Fortunae vexsillatio Gaesatorum Raetorum quorum curam agit Tabellius VictorThe Gaesati were a body of soldiers armed with a peculiar spear named an aesum. The following altar stone was found in Risingham.

"To the Goddess Fortune, the vexillation of Raetian spearmen have undertaken this under the management of Tabellius Victor the centurion."

Iovi Optimo Maximo vexillatio Gaesatorum Raetorum quorum curan agit Aemilius Ameilianus tribunus cohortis I Vangrionum"The Vangiones were a Belgic tribe from the upper Rhine. The First Cohort of Vangiones was a mixed unit of both horse and foot soldiers known as a cohors equitata, and were a nominal one-thousand strong (cohors milliaria). It is possible that they were split into two quingenary cohorts during the Hadrianic period as they are attested both at Chesters in Northumberland and also at Benwell in Tyne & Wear, both forts on Hadrian's Wall. They were apparently reunited as a single force at Risingham in Northumberland, beyond the Wall during the mid-third century." - from Roman-Britain.org.

"To Jupiter the best and greatest, the vexillation of Raetian Spearmen, under the command of Aemilius Ameilianus, tribune of the First Cohort of Vangiones [erected this]"

The same Raetian Spear unit had the following altar stone erected.

Iovi Optimo Maximo vexillatio Gaesatorum Raetorum quorum curan agit Iulius Victor tribunus cohortis I VangrionumA large fragment of a dedication slab also mentions this detachment.

"To Jupiter the best and greatest, the vexillation of Raetian Spearmen, under the command of Julius Victor, tribune of the First Cohort of Vangiones, [erected this]"

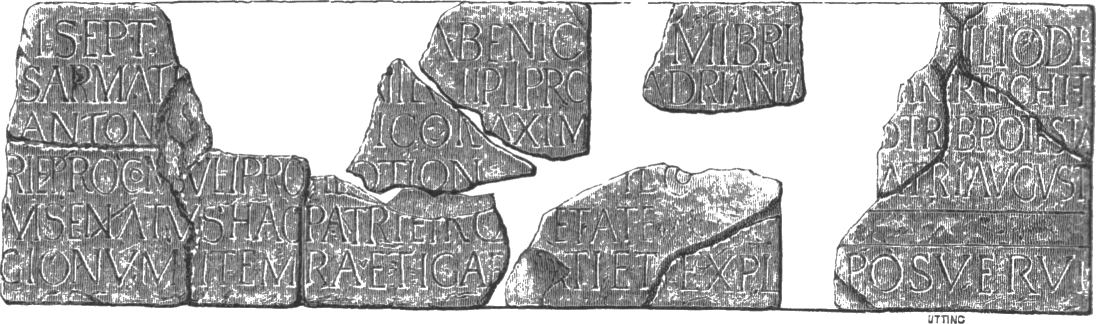

Imperatori Caesar divi Septim Severi Pii Arabici Adiabenici Parthici Maximi Britannici Maximi filio divi Antonini Pii Germanici Sarmatici nepoti divi Antonini Pii pronepoti divi Hadriani abnepoti divi Traiani Partichi et divi Nervae adnepoti Marc) Aurelio Antonino Pio Felici Augusto Parthico Maximo Britannico Maximo Germanico Maximo tribunicia potestate XVI imperatori II patri patriae proconsuli pro pietate ac devotione communi et Iuliae Domnae Piae Felici Augustae Matri Augusti nostri item castrorum senatus ac patriae pro pietate ac devotione communi curante legato Augustorum pro praetore cohors I Vangionum item Raeti Gaesati et Exploratores Habitancenses posuerunt devoti numini maiestati que eorumExploratores Habitancenses were a company of scouts from Habitancum, a Roman fort in Risingham. The following is from a stone, probably a Roman altar stone, being used as a lintel over a doorway at Jedburgh Abbey, which is just a few miles from Risingham. It was apparently taken from the fort at Cappuck.

"For the Emperor Caesar, son of the deified Septimius Severus Pius, conqueror of Arabia, conqueror of Adiabene, Most Great Conqueror of Parthia, Most Great Conqueror of Britain, grandson of the deified Antoninus Pius, conqueror of Germany, conqueror of Sarmatia, great-grandson of the deified Antoninus Pius, great-great-grandson of the deified Hadrian, great-great-great-grandson of the deified Trajan, conqueror of Parthia, and of the deified Nerva, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus, Most Great Conqueror of Parthia, Most Great Conqueror of Britain, Most Great Conqueror of Germany, in his sixteenth year of tribunician power, twice acclaimed Imperator, father of his country, proconsul, out of their joint duty and devotion, and for Julia Domna Pia Felix Augusta, mother of our Emperor, likewise of the army, Senate and country, out of their joint duty and devotion, under the charge of �, imperial propraetorian legate, the First Cohort of Vangiones, likewise the Raetian Spearmen and the Scouts of Habitancum, devoted to their divinity and majesty, set this up. "

Iovi optimo maximo, vexillatio Raetorum Gaesatorum quorum curam agit Julius Severinus triubnusJulius Severinus also erected a placque in honor of completing a bath house at Risingham. Finally, at Birrens (Blatobulgium), we have a highly ornamented alter, right, with the following inscription.

"To Jupiter the best and greatest, the vexillation of Raetian spearmen under the command of Julius Severinus the tribune [erected this]"

Marti et Victoriae Augustae. Cives Raeti militantes in cohorte secunda Tungrorum, cui pracest Silvius Auspex, Praefectus, fecerunt. Votum solverunt libentes merito.Birrens was a fort north of Carlisle. The Tungrians were a tribe who lived in the Belgic (northern) part of Gaul. Silvius Auspex also had altars to Minerva and the goddess Viradecthis erected at Birrens by the Second Cohort of Tungrians.

"Sacred to Mars and Victory the August. Raetian citizens, serving in the Second Cohort of Tungrians, commanded by Silvius Auspex the Prefect, erected this. They performed their vow willingly, deseservedly"

At set intervals along Hadrian's great wall, forts were established, the largest of which could accomodate a full cohort, or about 500 men. Inside were a headquarters building, the commandant's house, a hospital, granaries, baths, latrines, and barracks. Each barracks accomodated a century, or about 80 men, in 10 rooms, plus their centurians. Outside the fortress walls civilian settlements, the vicus, grew up providing services for the lonely soldiers, see the aerial view of a fort and vicus below. As with today's army posts and marine corps bases, these diversions included taverns, gambling dens and brothels. Some of the liaisons at the latter resulted in haplogroup G sons. Was one of those my many-times great-grand-daddy?

After years of service soldiers would take wives from the local population of Brigantes and Carvetii, settle down, and raise families. To encourage these soldiers to remain in the border regions after their retirement, which occurred after 25 years of service, the government would often provide free land to the veterans. Located along likely invasion routes, these veteran's villages provided a quick, well-trained, low-cost and well-motivated militia. Thus, non-native haplgroups were introduced and fostered in the border regions of England. These haplogroups included Middle Eastern strains, including E, G and J.

Under continual stress from foreign invasion, an evolution of Roman military organization occurred in the Third Century which resulted in the creation of a special border defence force, the limitanei, who were a "settled and hereditary" militia that were "tied to their posts." To the rear of these forces were the strategic reserve, the more thoroughly trained and heavily armed comitatensis, a mobile force designed to respond quickly to break throughs at the border. Because the limitanei were not meant to be involved in heavy fighting, these soldiers were granted plots of land to cultivate, which essentially turned them into part time farmers. So it may be that, in the years after the Raetian cohorts were first stationed at Hadrian's Wall, their sons and grandsons evolved into limitanei, provincal soldier-colonist-farmers manning the same walls as their fathers' had.

Over time, the quality of these border troops declined because of the poor conditions in which they lived in the impoverished and isolated towns of the frontier. As they became more thoroughly settled amongst the native populations, they lost their Imperial gloss and, as the Empire slowly receded they became as "British" as the descendents of Paleolithic hunters.

We have previously noted that present-day haplogroup G percentages in England show Lancashire and Cumbria with extremely low numbers, .5% and .0%, respectively, while the northeastern counties (Durham, Northumberland and Yorkshire) and East Anglia (Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire) have the highest, 3% and 4%. While this may be anything, it may indicate where Roman forces were stationed. Specifically I'm thinking of the coastal forts, the Saxonicum, built to repulse the Saxons in the latter years of the Empire.

Sequencing of five ancient Scythian remains indicate that none are haplogroup G, obviating the discussion below. The remains are R1a, R1b and Q1a.

We've previously discussed how our haplogroup, and specifically the L497 variant, may have been introduced during this time by Raetian recruits stationed on the northern borders of Britannia. Another group which has often been identified as a source of G-types in northwestern Europe are the Sarmatians, of the northern Caucasus and steppes of Russia. According to the Roman historian Cassius Dio, the Empereor Marcus Aurelius sent 5,500 cavalry from the Iazyges, a tribe of Sarmatians, presumed to be haplogroup G, to England. There is evidence of their occupations of forts along Hadrian's Wall and at Ribchester.

There is an apparent Romanian-Austrian-German-Swiss-Dutch-English axis to the G2a3b1 haplogroup's spread that at least appears to align with the Roman imperial border of the 1st to 5th centuries AD. In the 2nd through 4th centuries large numbers of soldiers drawn from "barbarian" populations just outside the Empire were stationed in the areas where we find so many DYS388=13 groups today: in northern Britain, from the Netherlands down to Switzerland along the Rhine river, and in Austria and Central Romania along the Danube.

This axis of the haplogroup's spread also aligns with the path of the invasions out of the steppes of Russia that brought down the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. The people of Ossetia, in the Caucasus, a predominantly G2a1a-type, consider themselves to be the descendants of the Alans, a Sarmatian tribe that dwelt on the Russian steppes, just north of the Caucasus. The Alans, along with the Vandals, invaded the Roman Empire in the 5th century and founded short-lived kingdoms in France, Spain and northern Africa. The G haplogroup may be a marker of Sarmatian ancestry, if the Ossetian theory is correct. DNA testing of known Sarmatians remains, however, is lacking. See more about the Sarmations below.

Other possible source P303 populations in the Caucasus were the Adyghe, Ubykh, Kabardians, Abkhazians, and Circassians. See Adyghe People.

| The Sarmatian's

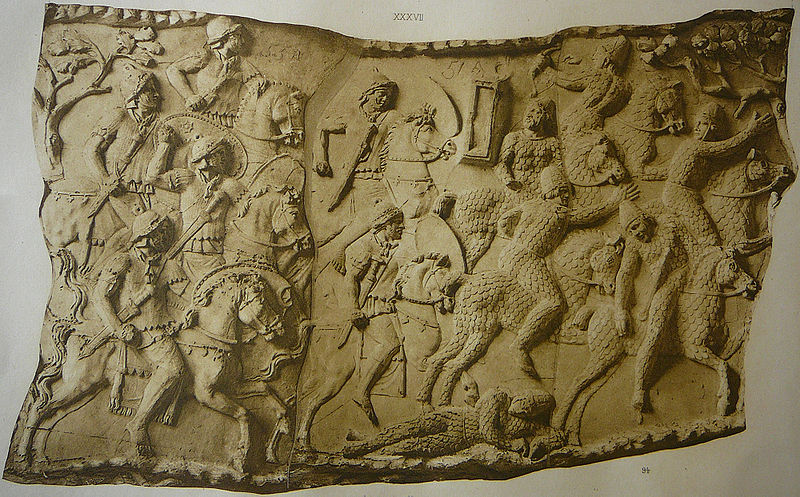

The Sarmations were a people of Central Asia, originally occupying a region from the Caucasus to the Don river on the Russian steppe. In the 4th century B.C. the Sarmatian's moved west into the Black Sea steppe, displacing the Scythians with whom they were related. Unlike the majority of steppe peoples, who were Turkic or Altaic, both the Scythian's and Sarmatiann's were Indo-Aryan in extraction and spoke an Iranian language related to Persian and Median. For their war with the Scythians, who fought as mounted bowmen, the Sarmatian tribes developed a fully armored warrior who rode an armored horse. Originally this armor was made of slices of horce hoof sewn to a leather jerkin in an overlapping fishscale pattern. Later metal scales were substituted. The riders also carried a leavy lance and a broadsword. Below the Roman army chases Sarmatian cavalrymen.  After displacing the Scythian's, the Sarmatians moved west, to Rome's eastern borders. The Empire first faced the Sarmatians in battle during the 1st century B.C. Iazygian tribes, who settled north of the Danube, had allied with King Mithridates of Pontus and Rome fielded a punitive expedition against them in 78-76 B.C. In the 1st century A.D., driven by the Huns, the Sarmatians moved west to the Hungarian plain and up against the Roman's Danube border. Sarmatian cavalry opposed the empereor Trajan in his conquest of Dacia in the 2nd century. Based on their experience fighting the Romans, the Sarmatians began to use Roman-style chain mail. The empereor Marcus Aurelius defeated a Sarmatian confederation of Alani and Roxalani tribes in 169 A.D. and again in 172. A peace was signed in 175 under which the Sarmatians were required to furnish the Roman army with 8,000 cavalry. The Empereor ordered 5,500 Iazyg warriors from the Danube region to Britain to guard Hadrian's Wall and the north; evidence of Sarmatian occupation have been found at forts along the wall and at a veterans' settlement at Ribchester [Bremetenacum Veteranorum] where the Ala Primae Sarmatorum was based. The Sarmatian's who remained on the steppes were conquered by the Huns and later absorbed by the Vandals. - from "Warriors on the Steppes" by Erik Hildinger |

We don't know if all 5,500 Sarmatian cavalry mentioned in Cassius Dio's history were actually sent to England since records and archealogical evidence exists for only 500 to a 1000. However, these Sarmatian military outposts certainly could have introduced hundreds, if not thousands, of their Y-DNA into Lancashire. There is evidence for these units in England for at least 160 years (241-400), implying that the sons and grandsons of the original cavalrymen were then serving. There are several tombstones at Ribchester [Bremetenacum] and one documentary reference describing the Sarmatian presence. At right is from the tombstone of an auxiliary cavalryman at Ribchester.

We don't know if all 5,500 Sarmatian cavalry mentioned in Cassius Dio's history were actually sent to England since records and archealogical evidence exists for only 500 to a 1000. However, these Sarmatian military outposts certainly could have introduced hundreds, if not thousands, of their Y-DNA into Lancashire. There is evidence for these units in England for at least 160 years (241-400), implying that the sons and grandsons of the original cavalrymen were then serving. There are several tombstones at Ribchester [Bremetenacum] and one documentary reference describing the Sarmatian presence. At right is from the tombstone of an auxiliary cavalryman at Ribchester.

"To the spirits of the departed (and) [...] decurion of the Sarmatian Wing." - RIB 595; tombstoneThe Sarmatians were the only military unit listed at Ribchester. Per lineam Valli meant in the vicinity of the wall [Hadrian's]. Ribchester is, in fact, 70 miles south of that location.

"This earth seals up Aelia Matrona, who lived for twenty-eight years two months and eight days, and Marcus Julius, son of Maximus, fifty years old. Julius Maximus, singularius consularis of the Sarmatian Wing, husband of an incomparable wife, and son of a most devoted father, placed this in memory of the most steadfast of companions." - RIB 594; 3rd century tombstone?

"To the sacred god Apollo Maponus, and for the health of our Lord and the Company of Gordians Sarmatian Horse at Bremetenacum, Aelius Antoninus, centurion of the Sixth Victorious Legion, from Melitanis, in charge of the Company and the Region, willingly and deservedly fullfilled his vow. Dedicated on the first day of September when our Lord Imperator Gordianus Augustus [Emperor Gordian (Imp. AD238 - 244)] - for the second time - and Pompeianus were consuls." - RIB 583; dedicatory inscription; AD241

"XL.

Dux Britanniarum.

Sub dispositione viri spectabilis ducis Britanniarum:

. . .

Item per lineam Valli:

. . .

Cuneus Sarmatarum, Bremetenraco [The Formation of Sarmatians at Ribchester]" - Notitia Dignitatum (circa 400)

| Other Sarmatians in the Notitia Dignitatum

The Notitia Dignitatum is a list of official posts in the Roman Empire, both civil and military, circa 395-425 AD. The section on the Western Empire is considered to be in the more recent end of that range. The first section shown is of officials in charge of laeti, communities of foreigners, in this case Sarmatians, permitted within the empire and given land for settlements. See Wikipedia for more about the laeti. The Notitia is incomplete and covers only Italy and Gaul. The last section shown is of commanders of military units in Egypt. XLII. |

During this same period Sarmatian troops under Roman command were also contributing their Y-DNA to the populations of Belgium, northwestern France, southern Germany and Austria. Further, during the collapse of the Western Empire, large numbers of Sarmatian and other barbarian invaders also left pockets of possible G-type settlers along their invasion route. The descendents of these groups may have been aboard the boats bringing the Normans to England in the 11th century. Other settlements in England, including that of the Huegenots in the 17th century, may have included this haplogroup as well