|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

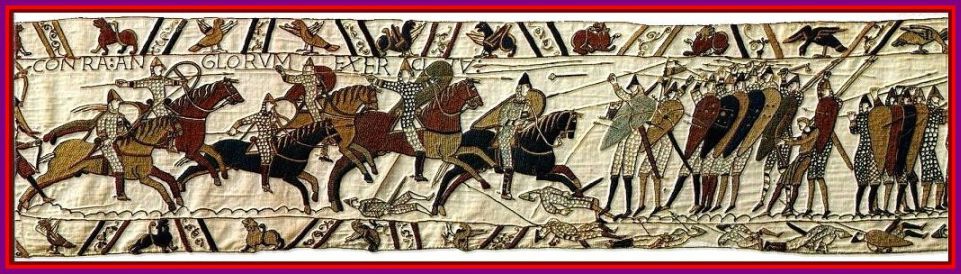

In 1066 Duke William of Normandy famously invaded and defeated the English army at Hastings.

The Norman Invasion is another point when haplogroup G-Z726 may have been introduced into England in relatively substantial numbers. Note that the remains of King Richard III were recently discovered. They were tested to be the same haplogroup as our family, G2. Richard was the last king in the Plantagenet line whose ancestor was Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, who married the daughter of Henry I. Geoffrey descended, through a junior line, from the Counts of Perche circa 936 AD. Perche was just south and east of Normandy. The county was bounded by the Sarthe river in the west and north, the Loir in the south, and the Eure in the east. The Gernet family descent is also via a family with roots in Normandy and Perche.

| Historical Timeline: The Norman Invasion, 1066 AD

Duke William claimed that King Edward, during one of his forced stays at the Norman court when the Vikings were ascendent, promised the throne to William upon Edward's death, he being childless. Whether this is true or not, William planned to act accordingly. When, upon the death of Edward, the Saxon lords predictably selected Harold, the most powerful of the English Barons, as their King, an invasion was only a matter of time, and the English knew it. Harold raised an army and awaited the assault in the south, but was called north by a Norwegian invasion. He won a brilliant victory over them at Stamford bridge, but then learned that William had landed during his absence. The English army met the Normans after a forced march south. It is a subject of debate whether Harold should have delayed the subsequent battle to rest his troops, but he probably felt that any time wasted gave William more time to secure his position. At this time Normandy was the most highly organized state in Europe and possessed one of its most professional armies. Its forces were characterized by armored cavalry, developed in France in response to the mobile tactics of Viking raiders in the north and Moorish invaders in the south. The Saxons, on the other hand, still employed heavy infantry deployed in a shield-wall. The Battle of Hastings, like Waterloo, was a near run thing. The Saxons had taken a strong position on an eminence and established the shield wall, with Harold protected by his housecarls, an elite infantry force. After numerous failed attempts by the Norman cavalry to break this defensive position, the Normans decided to try a feint. They attacked again, then retreated in apparent disorder. A number of the Saxon warriors, exhausted and now exultant at their seeming victory, broke ranks to chase the disappearing horsemen. On command the Normans reversed their course and fell on these disorganized units, slaughtering them in detail. The final defeat came when Harold was killed by an arrow. Norman rule would end a long era of foreign invasion and introduce feudalism to England.  At the time of the Conquest the population of England was estimated to be about 1.5 to 2.0 million. |

| Historical Timeline: Reign of Kings

After the Battle of Hastings William consolidated his power in the south. Recognizing the importance of London, he built the Tower of London to control the population of that city. This castle, painted white to enhance its visibility & dominance, became known as the White Tower. He also built a ring of fortresses a day's march from London to protect the city from attack, of which Windsor castle was one. Later he would attack the problem of northern England. |

The period immediately after the Conquest was a time of unhappiness and unrest, and Saxon England was perpetually on the verge or in the throes of rebellion. In the north a number of great men strived for control. The first was Earl Copsi, an old ally of Tostig, who was made earl by William in a period when his control in the south was still uncertain. Copsi, however, was quickly murdered by Oswulf, the son of the old Saxon Earl Eadwulf, who then maintained himself as earl until he too was murdered, by a brigand. Gospatric, a grandson of Earl Uhtred and cousin to Oswulf, also vied for the earldom and held it for a while after purchasing the right from King William. He could not, however, relinquish the habit of rebellion and sided with the Atheling, a prince of the old house of Wessex, in his attempt to eject the Normans.

At one point Northumbria was given by William to a Norman lord, Robert de Comines, but he and his small army were ambushed and destroyed before they could take power. Also by this time Waltheof, son of the old Danish Earl Siward, had come of age and was ready to retrieve his patrimony, leading the last, and most bloody, of the rebellions. The Scots also took every opportunity to seize lands while the north was in turmoil.

After these many uprisings and disturbances King William, having secured his position in the south, led his Norman army north to teach the Saxons what happened to those who defied his authority. The Norman's ruthlessly crushed the numerous rebellions in what became known as the "harrowing of the north," a vicious campaign which included an artificial famine brought about by Norman destruction of food caches and farming implements.

"Nowhere else had William shown so much cruelty. Shamefully he succumbed to this vice, for he made no effort to restrain his fury and punished the innocent with the guilty. In his anger he commanded that all crops and herds, chattels and food of every kind should be brought together and burned to ashes with consuming fire, so that the whole region north of the Humber might be stripped of all means of sustenance. In consequence so serious a scarcity was felt in England, and so terrible a famine fell upon the humble and defenceless populace, that more than 100,000 Christian folk of both sexes, young and old alike, perished of hunger." - from Orderic Vitalis, 1069This campaign, akin to Sherman's March to the Sea, left an unequalled devastation from which the north did not recover for many years.

"Throughout the winter and slaughtered the people . . . it was horrible to observe in houses, streets and roads human corpses rotting…for no one survived to cover them with earth, all having perished by the sword and starvation, or left the land of their fathers because of hunger… between York and Durham no village was inhabited." - from Symeon of Durham

Gospatrick was able to make terms with the Conqueror and ruled again for a few years as Earl, but once William had things firmly in hand Gospatrick was stripped of his title and exiled. William had married Waltheof, the son of the old Earl Siward, to his niece, Judith, in 1070 and gave him the Earldom in 1072. However in 1075 Waltheof once again became involved in revolt, this time in company with several Norman Earls. Defeated in battle, he gave himself up to William, who beheaded him. This was considered harsh, if not unfair. Norman knights involved in the rebellion merely had lands confiscated and were imprisoned. William was said to have been obsessed by guilt over this treatment of Waltheof, who became revered as a Saxon martyr.

Lordship of Northumbria subsequently passed through Bishop Walcher of Durham, an incompetent leader who was murdered in 1080, to Aubrey de Coucy, a Norman. By the way, the de Coucy family in France is the central focus of the history A Distant Mirror by Barbara Tuchman. Control of the north was so difficult, however, that de Coucy resigned the position. He was regarded as "of little use in difficult circumstances" of which there were plenty. It was only with the assignment of Robert de Montbray, or Mowbray, another Norman, in 1086 that a family powerful enough to control this region was found.

The actions of these great men were imitated at every level of society so that even in the meanest village some man, stronger and more ruthless than the others, dominated and exploited his neighbors.

Feudalism. Feudalism.

When Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine frontier into Roman Gaul, they came over as ein volk, each a single people ruled by a King from their own tribe. They were somewhat eglatarian with a very flat social structure. They were the Allemani, the Germani or the Burgundi. Feudalism, contrarily, was, in Norman Cantor's phrase, an "irresponsible kingship" in which mutual obligations between a leader and his warband replaced kinship. These Kings and Barons had no necessary blood relationship with the people they ruled and had, in fact, little concern for their welfare, hence "irresponsible." How did and why did feudalism arise? I'm no scholar, but the fact that relatively small Germanic tribes took over the government of an already large indigenous population may explain the initial kinship-to-kingship break. But more importantly, feudalism was a reflection of a weak central power that lacked the administrative structure to govern a large nation. Feudalism was characterized by the granting of hereditary fiefs in return for military service and political support. The nobles judged their King by how open-handed he was and they maintained their allegiance to the man that could provide them with power, wealth and position. In turn they maintained their positions by the same process, providing their own retinues with lands, revenues and titles. The size of their following reflected their importance and power. There was an inherit weakness in this plan, however. If the King or a Baron called upon his vassal, would he come? We're all familiar with the term, "the check is in the mail." With no other ties to bind the lord and vassal together than mutual obligation, each call would result in a kind of moral mathematics. That is, I owe my lord my support in the coming battle, but what are the odds that he will win? If he may not win, shouldn't I change my allegiance now or negotiate for a better deal? Marriage was a favored tactic to strengthen the tie between vassal and lord. |

The Mowbray's, like the de Coucy's and the de Montgomery's, who we'll discuss immediately below, were more than just a family name. They were a great clan whose power derived from their vast land holdings as well as access to and influence with the King. This power attracted many alliances with other families which were cemented through the bonds of marriage. The Gernet family probably counted themselves, originally, as part of the Montgomery family. After that family's fall the Gernet's attached themselves to the Mowbray clan through a marriage with a Mowbray daughter.

"The Norman upper heirarchy was not large. This elite group consisted of 22 honours or baronies which virtually controlled all of Normandy and contributed largely to Duke William and the invasion and Conquest of England. They were the Counts of Aumale, the Mortimers, the Giffards, the Ferrierers, the Counts d'Eu, the Tosnys, the Bisets, the FitzOsberns, the Warrens, the Marmions, the Grantmesnils, the Malets, the FitzGilberts or Baldwins, the Tancarvilles, the Vernons, the Beaumonts, the Paynels, the Aubignys, the Monforts, the Estouvilles, and the Gournays. These houses, or their offshoots, or lesser houses, would play an important role in English history for the next 3 centuries, and give rise to thousands of distinguished surnames throughout Britain. To the observant, it will be noticed that certain other significants familes are missing from this role of honour such as the Baliols, the Bigots, the Bullys, the de Lacys, the Mandevilles, the Mowbrays, the Montgomerys, the Pomeroys, the Percys, the St.Johns, the Tracys, the Skiptons, the Montfichets, and many others. The circumstances of the latter names and their subsequent rise to fame are variable and complex, and are bound up with the Norman protocols from which surnames emerged either in Normandy itself or later in the settlement of England." From - Shropshire and the Domesday Book.

In the meantime, after the harrowing of 1070, many of the lands previously occupied by Saxon nobles were given to William's Norman supporters. In about 1074 Count Roger of Poitou was made lord of lands in Essex, Suffolk, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, and Hampshire. However the principal part of his lordship was in what was then called inter Mersam et Ripam, "between the Mersey and the Ribble" rivers, now southern Lancashire.

These extensive holdings were grants made by William in reward for his father's assistance at the Battle of Hastings. Roger was the third son of the great Earl Roger de Montgomery II, the seignior of Mont gomerii in the arrondisement of Lisieux in Normandy and, later, the first Earl of Arundel and Shrewsbury. The Earl was William's Governor in Normandy during the campaign of 1066.

Earl Roger de Montgomery returned to Normandy with Queen Matilda and the Conqueror's eldest son, Robert, as William's representative and became head of the council that governed the Duchy in William's absence. This close bond with Robert, later Duke of Normandy, seems to have strongly affected the family's decisions when the throne became vacant on the death of William II, below.

| The de Montgomery Family

The family of Earl Roger of Arundel and his son, Count Roger of Poitou (sometimes Pictavencis, or in the West Riding as Roger le Poitevin). |

It was in early Norman times that the "constable" first appeared. The name came from a Latin phrase "comes stabuli" (a master of the stable), and was a very high office in Norman society. A century or so after the Conquest and certainly up to the Middle Ages, there were men called constables taking over the role of the tythingman.

Manorial courts, or Courts Leet, also gradually took over from the Sheriff's courts, and they elected those officials who were to serve for the next year on duties for the common good - ale tasters, bread-weigher and the constable. The latter was responsible for bringing wrong-doers to the court. Thus, and to the end of the 13th century, the constable was appointed by a local court but had responsibility for keeping the King's Peace and his laws.

In 1285 the Statute of Winchester introduced a system of "Watch and Ward," through watchmen in towns which had walls. The watchmen could arrest strangers during times of darkness. All the townsmen had an obligation to act as watchmen when called, and failure to act resulted in a spell in the stocks, where those arrested were kept. It also revived the "hue and cry" system, making the whole population responsible for pursuing a fugitive, and thirdly it required, through the Azzize of Arms, that all males between 15 and 60 to keep arms at his house, to be used whenever the High Constable of a Hundred might order.

The type of arms depended on a man's social standing. The poor would have bows and arrows, the rich had to have a horse, a sword, a knife and helmet, and these would be inspected twice a year by the two high constables appointed in each Hundred. These high constables were also responsible to the Sheriff of the county for selecting petty constables and watchmen.

This structure of law enforcement was maintained until 1829 when the Metropolitan Police were founded.

Before we discuss the written record of the Gernet family, let's look at the history and peoples of Normandy and Blois. As on a previous page, I have a section at the bottom of the page on the Sarmatians/Alans who swept through Europe. This is no longer relevant, they proved not to be haplogroup G, but I don't feel like destroying the write-up.

On previous pages we've discussed how G2a farmers had moved into Europe during the Neolithic and been subsequently marginalized by an invasion of R1a/b horsemen out of Russia. I am not aware of any ancient Y-DNA discovered in Normandy, but I expect that some small percentage of G2a-L497 survived to be subsumed into the new Celtic tribes. The modern-day population of Lower Normandy appears to be 71% R1b, 24% I, 12% I1a, 2% J, 2% R1a, and 1% G.

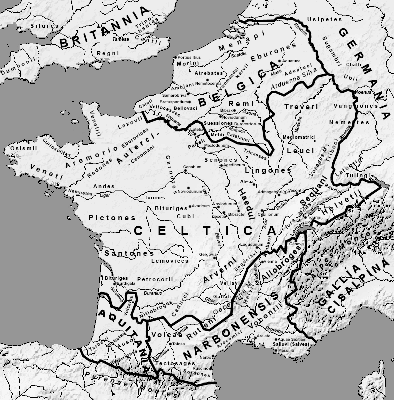

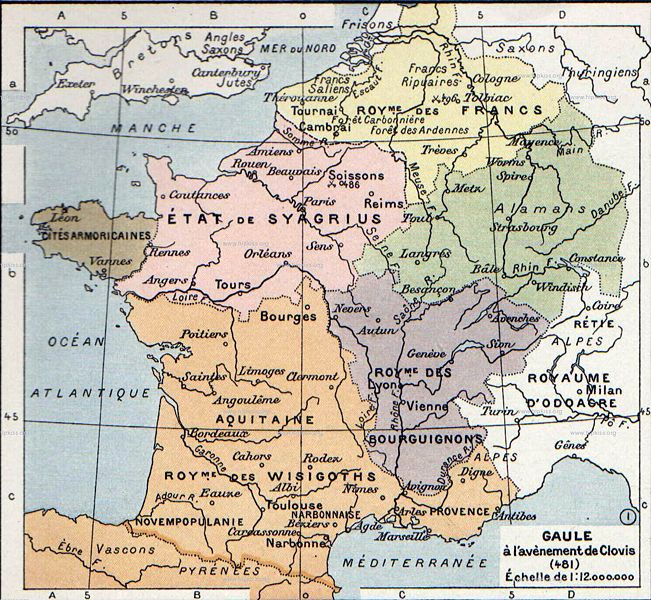

The region now known as France was known to the Romans as Gaul, or Gallia. Julius Caesar opened his famous "Commentaries" on the Gallic Wars with the line, "All Gaul is divided into three parts." These were the regions inhabited by the Belgae, in the north, the Aquitani, in the south, and the Celts (or Gauls) in the middle. The division line on the south was the Garonne river. That in the north were the Seine and Marne rivers. Other lands that we consider to be part of France today were known to Caesar as the Narbonnaise or Provincia Romana, today's Provence, and Cisalpine Gaul, the French-Italian border region.

The region now known as France was known to the Romans as Gaul, or Gallia. Julius Caesar opened his famous "Commentaries" on the Gallic Wars with the line, "All Gaul is divided into three parts." These were the regions inhabited by the Belgae, in the north, the Aquitani, in the south, and the Celts (or Gauls) in the middle. The division line on the south was the Garonne river. That in the north were the Seine and Marne rivers. Other lands that we consider to be part of France today were known to Caesar as the Narbonnaise or Provincia Romana, today's Provence, and Cisalpine Gaul, the French-Italian border region.

ParisThe Parisii of the region around Lutetia are discussed on the Celtic Origins page.

ChartresChartres is today the capital of the Eure-et-Loir department in France. In the Roman period the Chartrain, the area around Chartres, was inhabited by the Carnutes, a Celtic people who lived in the heart of independent Gaul in a territory between the Sequana (Seine) and the Liger (Loire) rivers. This territory had the reputation among Roman observers of being the political and religious center of the Gallic nations. The chief fortified towns were Cenabum, the modern Orleans, and Autricum, or civitas Carnutum, the modern Chartres. The great annual Druidic assembly mentioned by Caesar took place in one or the other of these towns.

The Carnutes were a dependency of the more powerful Remi, themselves a Belgic tribe who lived between the Mosa (Meuse) and Matrona (Marne) rivers. The Belgae were known to the Roman's as the bravest of the Gauls, which perhaps really meant the least civilized as they were furthest away from Mediterranean influences.

The region was organized as part of the imperial province of Gallia Lugdunensis, with its captial in Lugdunum, today's Lyon.

NormandyIn the Roman period Normandy was part of Armorica, the coastal region between the Loire and Seine. It was inhabited by several tribes of the Gauls, the Veliocassi, in the Vexin, the Lexovii, in the Lieuvin, the Unelli in the Cotentin, and in the Pays-de-Caux where Fecamp is located, the Caleti. These were the Caletae of Ptolemy and Calleti of Pliny. A Gaulish people of the Belgic tribe, noted in Caesar's history of his conquest of Gaul for the energy of their resistance, even after the defeat of Vercingetorix. Their chief towns were Caracotiunum, Harfleur, and Juliobona, Lilebonne, in the Roman province of Gallia Belgica. They occupied the coast from the mouth of the Seine to that of the Bresle, beyond which is Picardy. Its people today are known as the Cauchois.

This area became the Provincia Lugdunensis Secunda and the chief town was Rouen, Civitas Rotomagensium. There were six other civitates: Bayeux, Lisieux, Coutances, Avranches, Seez, and Evreux.

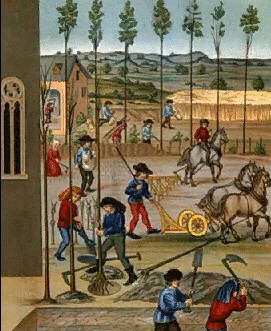

Gaul was famously conquered by Julius Caesar in 58 to 57 BC and the Romans ruled there for almost 500 years. This was an imperial province, ruled by a proconsul, but the Celts were allowed to keep their own self-governing institutions. The population probably remained predominately Celtic, though now heavily overlaid with Roman culture and language. The villa-system of agriculture, described earlier for Roman Britain, would have applied here as well. An excellent book, "The Civilization of the Middle Ages" by Norman Cantor, perfectly describes how, in the later Roman empire, these villas morphed into the fortified villages of the early middle ages, and how the Roman cataphracti equos, a heavily armored cavalry, became the model of the medieval knight.

Barbarian incursions out of Germany into Roman territory occurred even during the height of Roman power and it eventually became policy to encourage Germanic settlement within the empire as a means of replenishing and invigorating a dwindling population.

| The Germanic Tribes

The word German was Latin and originally described a single tribe, the Germani. Another tribe, the Allemani, was the origin of the French and Spanish name for this people. The Germans described themselves as piuda, the people. The word Deutsch only arose in the 9th century. Ethnically, the Germans were a Scandavian people who inhabited the southern shores of today's Norway and Sweden, Denmark and northern Germany. They pushed south looking for arable land as their population swelled. A cooling period between 600 and 300 BC adversely affected growing conditions and exacerbated this southern movement. By the 5th century AD Germanic tribes populated the entire Roman border from the North Sea to the Black. The Romans engaged in many wars with the German people and, at the height of their power, they controlled present-day Germany as far east as the Elbe river. However, after the disaster of the defeat of Quintilius Varus in the Teutoburg Forest, the Emperor Augustus pulled the legions back behind a defensible border based on the Rhine and Danube rivers. After this most of Rome's wars with the Germans were in the nature of retalitory raids. Later a forward defense was established with two provinces, Germania Inferior and Germania Superior, on the eastern shore of the Rhine. |

In the 4th and 5th centuries AD the pressure of westward movement on the Roman frontier became overwhelming. During the collapse of the western half of the Roman Empire, the Franks, a Germanic people, took possession of Gaul.

The Franks were a confederation of Germanic tribes, including the Salii, the Chatti, and the Sicambri, who, in the Roman period, occupied the eastern shore of the Rhine from Mainz to the sea. According to the "Chronicle of Fredegar," the Franks believed they were descendents of the Scythians or the Cimmerians, a tribal group that clustered around the Ukraine, though many peoples claim such an origin. Archaelogical evidence indicates that the Franks did originate in the region around the mouth of the Danube river, on the Black Sea, an area known to the Romans as Scythae Minor, so the assumption is not totally without merit. The Franks had migrated to the region of the Rhine by the 1st century BC. St. Gregory of Tours claimed the Franks came from Pannonia, approximately today's Slovakia/Hungary, which may have been a stop on their western migration.

The Franks claimed that their name came from an early leader, Franko. This name may actually be derived from the word franca, meaning javelin or lance, just as the name for the Saxons derived from a weapon, the saxe, a kind of axe. The throwing axe of the Franks was known as the francisca, but this was probably a later naming. The Frank's language was Germanic, similar to Old Dutch.

The Franks were first mentioned circa 50 AD in the Tabula Peutingeriana as the Chamavi qui est Franci, but members of Frankish subtribes engaged Julius Caesar in his conquest of Gaul in 55 BC. In the 3rd century the Franks were settling in Belgic Gaul on the Meuse and Scheldt rivers. The Romans were unable to expel them and eventually accepted them as foederati, allies. Rome granted a large part of the province of Gallia Belgica to the Franks, which became known as Francia.

During the great collapse of the Rhine border in 406 the Franks, under their King, Merovech, aided the Romans in trying to halt the Gothic onslaught. In this they failed, but it is unclear how this affected the Franks. The Visigoths apparently skirted the Frankish lands and continued south, where they established kingdoms in Acquitaine and Spain. The Franks gradually took control of most of Gaul north of the Loire valley and east of Aquitaine, continuing to support the Romans who, with Frankish help, maintained control of Paris until 486.

The Franks, like so many other migrating tribes, would have picked up G2a populations along the way. These may have been descendents of Otzi's people of the Tyrol or Raeti cohorts stationed in Upper and Lower Germania.

Six "high-status" graves dated to circa 670 AD, from the middle years of the Frankish kingdom, were discovered in Ergolding, Bavaria.

Six "high-status" graves dated to circa 670 AD, from the middle years of the Frankish kingdom, were discovered in Ergolding, Bavaria.

"Men from the grave 244 (marked 244A to 244F) were buried together into a single wooden burial chamber. Individuals found in the western part of the chamber (244A, 244B, and 244C) lied straight on the back, body-by-body, and all 3 men were buried with swords, spears, shields, and spurs, like heavily armored mounted warriors (9). Historic value of the artifacts found in the grave 244 makes this place one of the richest Bavarian burial sites from the late-Merowig period (9). The grave 244 dates to the period around 670 AD. The eastern part of the burial chamber with the individuals 244D, 244E, and 244F was robbed and therefore no valuable artifacts were found."Four of the burials contained R1b-type remains, but two burials were typed as G2a. The G-type burials were amongst those looted. Were all of these men Merovingian/Frankish knights? In the 6th century Bavaria was under the dominion of the Franks, who regarded the region as a buffer against the Avars and Slavs. These knights may have been casualties of this border warfare.

| Frankish Culture

The Franks were a Germanic people, but more importantly a tribal people. That meant that they were basically eglatarian and intensely rural. The Gallo-Romans they now interacted with were, in constrast, highly stratified socially and much more urban. Women had a more significant, and more equal role in Frankish society; divorce was allowed, female inheritance was common, and women had equal rights in raising their children. After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the west, the word Frank became almost a synonym for Europe. In Arabic the word is infranji and in Persian farangi. The noble qualities the Franks thought they possessed, of being open, forthright and sincere, came to be called, in English, frank. The word also means free, as in the "franking" privilege of sending free mail, or as in "franchise," which is the grant of a privilege or immunity. See the excellent website at Francia, 447-Present for more. |

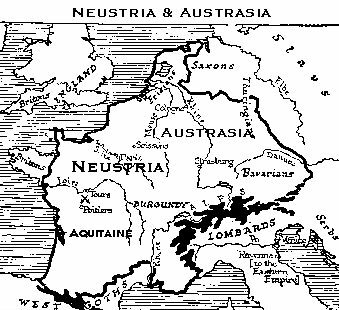

In the immediate post-Roman period northern France, above the Loire, was part of the kingdom of Syagrius, a Roman administrator. However in 486 he was defeated by the Frankish King, Clovis, who incorporated the entire region north of the Seine into the Merovingian kingdom of Neustria. Clovis subsequently conquered the Gallo-Roman-Alan population of the Loire valley, the Burgundians of the Rhone valley, and the Goths of Acquitania.

In the immediate post-Roman period northern France, above the Loire, was part of the kingdom of Syagrius, a Roman administrator. However in 486 he was defeated by the Frankish King, Clovis, who incorporated the entire region north of the Seine into the Merovingian kingdom of Neustria. Clovis subsequently conquered the Gallo-Roman-Alan population of the Loire valley, the Burgundians of the Rhone valley, and the Goths of Acquitania.

Clovis chose Paris as his capital. The western part of his kingdom became known as Neustria. It comprised the Seine and Loire country and the region to the north. The principal towns were Soissons and Paris. The eastern portion of the Frankish realm became known as Austrasia. Subsequent dynastic struggles ensured that these two regions remained in almost constant warfare. In the first centuries after the Frank's conquest, Gallo-Roman society continued to function, and to influence the Frank's culture. It was at the Loire river boundary, just south of Chartres, that the Frankish influences of the north and the Gallo-Roman influences of the south had their chief contact. This mix created modern France. However, it did not stop the decline of Roman culture which, by the 7th century, was a dim memory.

The fortunes of Clovis' family, known to history as the Merovingians, waxed and waned, but in the 8th century the mayor of the palace of the King of Austrasia, Pepin, the true power behind the throne, made himself King and united the two regions. His son, Charlemagne, took the Kingdom to new heights, conquering most of Germany, northern Italy, and Catalonia in Spain. The Pope, who was mightily impressed, crowned him as the new Roman Emperor in 800 AD. By the way, the real Roman Emperor, then living in Constantinople, was not amused. Another by the way, just to understand the state of learning at this juncture, Charlemagne supposedly never learned to read or write.

Charlemagne's son, Louis, divided this great empire to appease his three sons. That, of course, ensured continual warfare. The realms were Francia Occidentalis, today's France, ruled by Charles the Bald, Francia Orientalis, Germany, ruled by Louis, and Francia Media, a "sliver" kingdom that divided those two, running from the Netherlands to northern Italy, ruled by Lothar.

The later Carolingian King's were no better at running an empire or controlling their nobles than the Merovingians had been. France soon fell apart into a mish-mash of counties, duchies, and seigneuries ruled by over-powerful men. The domains actually governed by the King fell to just those lands surronding Paris. At the same time, and undoubtedly contributing to the decline, Europe suffered three major invasions; from the east by the Magyars who got as far west as Orleans before settling in Hungary; from the south by the Muslims who swept through southern France before settling in Spain; and from the north by the Vikings who plagued the Seine river valley and remained to settle Normandy.

See also Successors of Rome: Francia, 447-Present for an outstanding review of the Frankish kingdom.

Two regional powers that arose in France in the 9th and 10th centuries are of interest to us, Blois and Normandy.

The County of Blois The County of Blois was centered on the town of Blois, on the Loire river. The region is one of the most beautiful in the world. The extent of the county varied over time and the northern portion, bordering on Normandy, was sometimes alienated as the County of Chartres. Its greatest threat was from the Count of Anjou, to the west. The King, who personally controlled only the the Ile de France, to Blois' east, was at this time little more influential than the Counts. In the 10th century the ruling family of Blois gained the County of Champagne, greatly increasing their power.

The County of Blois was centered on the town of Blois, on the Loire river. The region is one of the most beautiful in the world. The extent of the county varied over time and the northern portion, bordering on Normandy, was sometimes alienated as the County of Chartres. Its greatest threat was from the Count of Anjou, to the west. The King, who personally controlled only the the Ile de France, to Blois' east, was at this time little more influential than the Counts. In the 10th century the ruling family of Blois gained the County of Champagne, greatly increasing their power.

Chartres was on the far northern edge of the county, on the Eure river. The region was agriculturally bountiful and became known as the "granary of France." The city was founded by a Gallic tribe called the Carnutes, and known to the Romans as the Autricum.

Even in ancient times Chartres had been a center of religious worship, first by the Druids and then, in a church built in the 4th century, by the early Christians of the Roman Empire. In 743 this cathedral was destroyed by Hunaud, the Duke of Acquitaine in one of the incessant wars of the period. A subsequent edifice was burned by the Vikings, as was the rest of the town, in 858. Rebuilt, the church was again burned, in 962, restored, and then completely destroyed in 1020. Then, from 1028 to 1037, Bishop Fulbert had a great cathedral built. It was 105 meters long by 34 meters wide, had two towers and a wood framed roof. However this building too was destroyed to be replaced by the cathedral we know today, the largest in Europe and one of the great marvels of the world. I suspect that it was this catastrophe and rebuilding that inspired Ken Follet's novel "Pillars of the Earth," about the construction of an English cathedral.

In the 9th century the countship of Blois was held in fee by the Margrave of Neustria, Robert the Strong, the missus dominicus of the Loire valley, also known as the Duke of France and Count of Paris. He spent most of his career attempting to hold off Viking attacks in the Seine valley. These Scandanavian raiders had first appeared in the Seine in 841. They settled around the mouth of that river as a convenient jumping off spot for their raids on England, France, Brittany and southern Europe.

Robert was succeeded by his son, Odo, who was King from 888 to 898. Louis the Simple, of the Carolingian line, then ruled, only to be replaced by Odo's brother, Robert, who had ruled the territory between the Seine and the Loire, from 922 to 923. He was succeeded by his son-in-law, Raoul of Burgundy, while Robert's son, Hugh the Great, inherited the vast Loire domains and supported the Carolingian candidate for the throne to spite Raoul. Hugh's son was Hugh Capet who became King in 987, the first of a long line of Capetian monarchs.

In about 940 the County of Blois was enfeoffed to the family of Theobald, who became the vassal of Hugh the Great, Duke of France. Then, in 987 when Hugh Capet became King, they became direct vassals of the crown. They emerged as one of the most powerful feudal lords in France and united Blois with Touraine and Chartres, and eventually Champagne.

| The Counts of Blois

Count Theobald I (c910-977) Thibaud. The son of Theobald "the Elder" of Tours. He was a vassal of Duke Hugh who held Chinon, Saumor and Bourgueil. Theobald the Younger reigned in Blois from 928 [940?] to 978. Sometimes called "the Cheat" because of the means he used to acquire Touraine and Chartres. He also held Dunois. While nominally a vassal of the Dukes of France, his increasing power allowed him to act autonomously. He married Ledgard, the daughter of Herbert II, Count of Vermandois and Champagne. She, apparently, had originally been the wife of Duke William I "Longsword" of Normandy. The Count made the mistake of attacking Normandy in 962 and, while initially successful, he did not get support from his suzerain, Hugh Capet, whom he had spurned, and was, in the end, heavily defeated. He died on 16 January 977. Count Odo I (c940-995)Eudes. He reigned in Blois from 978 to 995. His sons, Theobald and Odo, both reigned in turn. Count Theobald II (c980-1004)Thibaud. He reigned in Blois from 995 to 1004. Count Odo II (983-1037)Eudes. Theobald II's brother, he reigned in Blois from 1004-1037, and in Champagne from 1019 to 1037. With the accession of Champagne the Counts of Blois had encircled the Royal domain of the Capets. Odo was one of the most warlike barons of a warlike time, adding the county of Troyes to his dominions. He disputed the crown of Burgundy with the Emperor, Conrad the Salic, and perished in 1037 while fighting in Lorraine. Through political manipulation the Capets ensured that succeeding Counts divided their realm between sons. Count Theobald III (1019-1089)Thibaud. The son of Odo II, he reigned in Blois from 1037 to 1089. His brother, Stephen, reigned in Champagne from 1037-1048. Stephen's son, Odo, then ruled Champagne from 1048 to 1063. Theobald lost Tours to the Counts of Anjou, but, using his influence with the King of France, gained control of Champagne from his nephew and reigned there from 1063 to 1089. Young Odo then went on to serve in the army of William the Conqueror, fought at Hastings, married William's sister and became Count of Aumale and Holderness. Count Stephen Henry (1047-1102)Etienne-Henri. He reigned in Blois from 1089 to 1102. His brothers, Odo and Hugh, reigned in Champagne from 1089 to 1125. He married Adela de Normandie at the cathedral of Chartres. She was the daughter of William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy and King of England. He was one of the leaders of the 1st Crusade, along with Robert Curthose of Normandy. He returned home early, however, and his wife browbeat him into a second pilgrimage, where he was killed in 1102. Theobald IV "the Great" (1093-1152)Thibault. He reigned in Blois from 1102 to 1152, and in Champagne from 1125 to 1152, finally reuniting the counties and bring the family to the zenith of its power. His brother, Stephen, usurped the English throne and reigned during the Anarchy as Stephen I. Another brother, Henry, became Stephen's powerful ally as the Bishop of Winchester. His sister, Mahaut, died in the disaster of the White Ship along with Henry I's son, the heir to the English Throne. |

Normandy [Normandie to the French and Normaundie to the Normans] lies on the English channel, bordered by Brittany, Anjou, Maine, Blois, and Flanders. It is split by the Seine river which forms a 12 kilometer wide estuary at its mouth. The coastline to the north, in the Pays de Caux, consists of high chalk cliffs. South of the Seine, the coast of Calvados consists of rocks and beaches. The penisula of the Contentin is sandy on the eastern side and granite to the west.

The first recorded Viking raid in France occurred in 820 and in 841 the city of Rouen was looted and burnt. In 845 the Vikings rowed up the Seine and attacked Paris, then repeated the attack three more times in the 860s, leaving only when they had acquired enough loot, or bribes, to satisfy them. In 864 the French established a standing army of cavalry to ward off the fast-moving invaders, but this was only partially successful. In 884 Sigfred, then leader of the Danes, demanded a bribe from the new King, Charles the Bald. Charles refused and the Danes attacked the Seine valley with 700 ships carrying more than 30,0000 men. From 885 to 886 Paris lay under siege, and Le Mans and Chartres were pillaged.

| Who Were the Vikings?

The recorded history of the Vikings began in 793 with their raid on the abbey church on Lindisfarne island, off the northeastern coast of Yorkshire, England. The Viking expansion that so troubled Europe was probably tied to increases in population and the lack of arable land for new farms. It ended with the establishment of royal authority in the Viking home countries in the 11th century. Denmark, based on the Jutland penisula, the island of Zealand and the southern part of Sweden, was the best organized and most powerful of the Viking states. For a thirty year period early in the 11th century its King, Canute, ruled both Denmark and England. The Vikings who invaded and made Normandy their home in the 800's were mainly Danes, though those of the Contentin penisula were Norwegians coming out of their colonies in Ireland, and those of Bessin, just east of the Contentin, were Danes from England. As Scandanavians, the Vikings and their direct descendants among the Normans, were haplogroup I, and therefore not related to family.

|

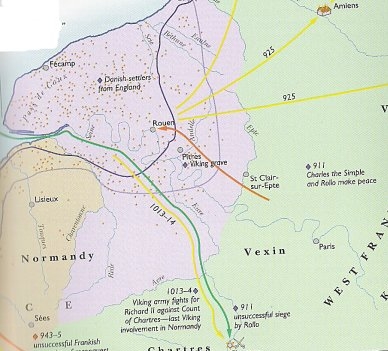

In 887 a Norwegian, Rolf Ragnvaldsson, became the leader of the Danes on the lower Seine. In 911 the Vikings under his command pillaged the lower Seine Valley and attempted to besiege Chartres, without success, but his army was such a threat to the Seine valley, that Charles, King of the Franks, known to history as "the Simple," negotiated a treaty at St. Clair-sur-Epte to give these Nordic warriors lands in France along both sides of the lower Seine, later known as le haute Normandie, nominally a fiefdom under the French crown, in hopes this would stop their destructive attacks on his kingdom. While Rollo, now Jarl of Rouen (the title of Duke did not come into use until 1000), did prevent other Vikings from raiding in the region, the vigor of the new Norman state ensured that war would be frequent along the marches with Blois, Anjou and Maine. See The Making of the Duchy of Normandy and The Vikings in Normandy.

In 887 a Norwegian, Rolf Ragnvaldsson, became the leader of the Danes on the lower Seine. In 911 the Vikings under his command pillaged the lower Seine Valley and attempted to besiege Chartres, without success, but his army was such a threat to the Seine valley, that Charles, King of the Franks, known to history as "the Simple," negotiated a treaty at St. Clair-sur-Epte to give these Nordic warriors lands in France along both sides of the lower Seine, later known as le haute Normandie, nominally a fiefdom under the French crown, in hopes this would stop their destructive attacks on his kingdom. While Rollo, now Jarl of Rouen (the title of Duke did not come into use until 1000), did prevent other Vikings from raiding in the region, the vigor of the new Norman state ensured that war would be frequent along the marches with Blois, Anjou and Maine. See The Making of the Duchy of Normandy and The Vikings in Normandy.

In 911 Rollo controlled the old county of Rouen, the area in purple in the map to the right. This included the Pays de Caux, Comte d'Eu, Pays de Brai, the Roumois and the Vexin Normand. In 924 he took Bessin, the region now known as Calvados, and in 933 his son, William Longsword, took Contentin and Avranchin, completing the conquest of most of what we know today as Normandy.

The map below indicates the generally sparse Scandanavian settlement in the southern parts of the Duchy. However, even in the regions of heaviest colonization, around Fecamp for example, I suspect the Danes were still in the minority, though very much in the authority.

Most of the Viking settlers would have been bachelors, young men seeking both land and wives. Even those men who had left families behind in Scandanavia would have been unlikely to sail back to bring them to Normandy. Within two generations the Normans, having intermarried with the French locals, had adopted the Franks' language, religion, laws, customs, political organization and methods of warfare. They had become Franks in all but name, for they were now known as Norman's, men of Normandy - the land of the Nordmanni or Northmen.

By the middle of the 11th century Normandy was one of the most powerful states in Christendom. Desire for conquest, in conjunction with limited available land, led many Norman's to pursue military goals abroad: to Spain to fight the Moors; to Byzantium to fight the Turks; to Sicily and southern Italy in 1061 to fight the Saracens; and of course to England in 1066.

| The Dukes of Normandy

Rolf Ragnvaldsson (c860-932) Rolf was baptized in 912 and became known as Rollo or Robert, the first Duke of Normandy. He reigned from 912 to 927, passing the Duchy to his son before his death. His son was William. William Longsword (c900-942)He reigned from 927 to 942 and generally allied himself with Hugh the Great, Duke of France. William was killed on 17 December 942 in connection with a war he was waging with Arnolph, the Count of Flanders. His son was Richard. Richard I "the Fearless" (c935-996)He reigned from 942 to 996, coming to the throne as a minor. He entered a preferential alliance with Hugh the Great and married Hugh's daughter. Despite this the Counts of Blois pressured his borders. Richard II "the Good" (c965-1027)He reigned from 996 to 1026 and built a strong adminstrative state. He fought border wars with the Count of Anjou and Count Odo of Blois. Note that through this period Danish Vikings had continued to use Normandy as a base for their raids on England. King Ethelred the Redeless of England requested Richard's aid in stopping them and sealed their alliance by marrying Richard's sister, Emma. Their son was Edward the Confessor who, upon his father's defeat by the Danes, took refuge in Richard's court. His mother, Emma, subsequently married Canute, Ethelred's successor as King of England. Their son was Hardicanute. Richard's sons were Richard and Robert. Richard used the Danes living in Normandy to aid him in his wars with Blois and, after Count Odo's defeat, the pillaged the Loire and Eure valleys. Richard III (997-1027)Richard's father had chosen to divide the Duchy between his sons, but Robert, the younger, was quick to rebel and Richard died under mysterious circumstances. Richard reigned from 1026 to 1028. His son, Nicholas, was relegated to a monastery, first to Fecamp and then Saint Ouen in Rouen, by his uncle, who succeeded as Duke. Robert "the Devil" (999-1035)Richard's brother, he reigned from 1028 to 1035. In premonition of his son, he attempted a great maritime expedition against England to reinstate his cousin, Edward, to the throne, but the fleet was dispersed by a storm. He died in Nicaea in July 1035 while on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. His illegitmate son was William. William II "the Conqueror" (1028-1087)A minor and the illegitimate son of Duke Robert and Herleva, the daugther of Fulbert "le polinctor," a tanner. William 'the Bastard' succeeded to the Dukedom at the age of seven or eight, his father, Robert "the Devil," having died without a legitimate male heir. For the next twelve years of his minority the Duchy was in a constant state of anarchy. The rebellion of the Barons came to a head in 1047 when the whole of lower Normandy rose against him. With the help of his feudal overlord, King Henry I of France, William, aged twenty, crushed the revolt on the field of Vales Dunes, near Caen. The castles of the rebellious Barons were razed and the nobles never challenged the duke's power again. William's mother, Herleva, later married Herluin, Vicomte of Contreville. They had two sons, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and Robert, Count of Mortain. These two half-brothers of William remained close to him all of their lives and were at the Battle of Hastings. William reigned from 1035 to 1087. He married Matilda, daughter of the Count of Flanders. |

Allied with the Visigoths in the invasion of Gaul were the Alans, a Sarmatian people of the Caucasus. We've already discussed how Sarmatians may have introduced the G2a haplogroup into Britain during the Roman period. They also brought their genes to northwestern France. The movement of this haplogroup into northwest Europe is usually ascribed to the barbarian invasions of the 4th and 5th centuries AD, but the Sarmatians were known to have had settlements in Belgium, Switzerland, southern Germany and Austria, France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy even before the collapse of the Empire. Many of these were laeti settlements, in which Rome provided admission to the empire and a grant of lands to barbarians in return for the promise of loyalty and the obligation to supply recruits to the Roman army. In France there was a population of at least 35,000 Sarmatians, or about 2% of the estimated population.

| Alan Settlements in Gaul

In the winter of 406 the Vandals crossed the Rhine river border near its juncture with the Main and invaded the Roman province of Gallia, modern day France. The Franks, who had crossed the Rhine earlier and joined the Empire's service in exchange for land, resisted them. The Vandals were facing defeat when the Alans, a Sarmatian people, came to their rescue. After this disaster Roman officials opened negotiation with the barbarians and convinced one of the Alan commanders, Goar, to enter Roman service. "Interea Respendial rex Alanorum, Goare ad Romanos transgresso, de Reno agmen suorum convertit, Wandalis Francorum bello laborantibus, Godigyselo rego absumpto, aciae viginti ferme milibus ferro preemptis, cunctis Wandalorum ad internitionem delendis, nisi Alanorum vis in tempore subvenisset."Most historians identify these Alans with those settled by the Emperor Gration in Pannonia circa 380. Pannonia included the current territories of the western half of Hungary with parts in Austria, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Slovakia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Goar's followers were eventually settled in forward locations in northeastern Gaul, strategic to the defense of that province, including northern Switzerland. The other Alans, and their Vandal allies, continued their raids, eventually passing into Iberia.  Earlier a variety of Sarmatian peoples, include Alans, Roxolani and Iazyges, had settled within the Empire as military colonists, or laeti. In Gaul they had been settled from Amiens in the north through Sermaise (Oise), Sermoise (Aisne), Rheims, Sermiers (Marne), Semarize les Bains (Marne), and Langres in the south. These settlements were positioned to protect important roads and cities. Goar's followers were settled forward, towards the threat to the east, perhaps in Allains (Somme), 30 miles east of Amiens. Twenty-five miles to the southeast is Alaincourt (Aisne). Further to the southeast is Alland'huy (Ardennes) and another village named Alaincourt (Ardennes). To the south of Rheims are Allancourt (Marne) and Sampigny (Marne). Another Sampigny was established thirty miles east of Sermaize les Bains. The word Sampigny was derived from the Alan name Sambida. Near Metz is Allamont (Meurthe-et-Moselle) and to the south of Metz is Alaincourt-la-Cote (Meurthe-et-Moselle). To the south of Toul are Alain (Meurthe-et-Moselle) and Aillianville (Haute-Marne). There is another Alaincourt (Haute-Saone) east of Langres. Other Alan placenames in France include: Twenty-five miles northeast of Lyons are three small towns, Alain, Aleins and Alaniers. Twenty-five miles east-northeast on the outskits of Bourge is the town of Allaigne. Across the border in Switzerland, near Geneva is a river formerly called Aqua de Alandons and just north of Lausanne is the town of Allens. - from "A History of the Alans in the West" by Bernard S. Bachrach. The Visigoths, who had followed the Vandals and Alans in crossing the Rhine border, settled in southern France and northern Spain. In 442 Flavius Aetius, dux et patricius, moved some of the Alans, under their king, Goar, to the Orleans region to counter Visigothic intrusions out of Aquitaine. The Alans also moved into nearby Armorica, where they soon replaced and intermarried with the local land-owners. Armorica was the part of Gaul that included the Brittany peninsula and the territory between the Seine and Loire rivers, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic coast. In 451 the Alans, under their king Sangiban, joined the Romans to resist Attila's invasion of Gaul, fighting at the Battle of Chalons. In 481 the Loire valley was part of a Gallo-Roman state under the command of Syagrius, the last of the Roman dux. After the fifth century, and the conquests of the Franks under Clovis, the Alans of Gaul were subsumed in the territorial struggles between the Franks and the Visigoths, and ceased to have an independent existence. |

|

Alan Settlements in the Caucasus

The Alans not involved in the movement out of the Steppes and into the West were, in the face of further waves of invaders from the east, to retreat from the steppes into the Caucasus mountains. As a result, the Alanian population of the Northern Caucasus increased considerably. They eventually founded the regionally powerful kingdom of Alania. In the 11th century, however, they were overwhelmed by the Mongols. They re-emerged as the Ossetians, living in Georgia and southern Russia. |