|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

The Heysham family of England can trace their origin to William Highsame, a merchant born in about 1570 in Lancaster. I think it not unreasonable to connect them to John de Heysham [or Hesham], a merchant and bailiff of that town in the 13th century. However, they have long claimed that they find their earliest origins in the Gernet family of Normandy, a cadet branch of which were the Lords of the manor of Heysham from the 12th century. The claim, of course, is that the Gernet's of Heysham assumed the surname to show their ownership of the village and to differentiate themselves from the senior line of the Gernet family, who lived in Halton, Lancashire. The Gernet, or Grenet, family came to England during the Norman Invasion of 1066, or very soon thereafter. They came from Fecamp (pronounced "fee-kay") in Normandy. There is also a Grenet family in the region around the cathedral city of Chartes, known as the Chartain, in what was then the county of Blois. Which was the earlier settlement and whether these two families were related, I do not yet know. If this relationship is true, then we may have a Norman-French heritage, assuming I can prove a relationship between the Heysham's of Lancashire and the Heesom's of Yorkshire.

Gernet AncestorsAs I interpret it, members of the Gernet family came to England around the time of the Conquest and were first given estates in the southeast of the country, notably in Essex and Hampshire. Later, a branch of this family received lands in the north, in Lancashire. This group then divided into at least four sub-branches: the Gernets of the manors of Halton (the senior line), of Heysham, of Caton, and of Lydiate. Over time their locative names, at least for the junior branches, became their surnames, that is "de Heysham," "de Caton," and "de Lydiate."

Footnote: "In no county in England do the names of the lands so much correspond with the surnames of their owners, as in Lancashire." - from "History of the County Palatine of Lancaster" by Edward Baines and William Robert WhattonThe Gernets of Halton may have also produced a line of "de Haltons," though they tended to keep the Gernet name the longest.

The Heysham family traces its origins to the Heysham branch of that Norman family. In the following reference it is even implied that the Heysham name was more ancient than that of Gernet, though I have no where else found this.

"the Lords of the Manor of Heysham acquired the surname of Cornet, eventually transformed into Gernet, in which name the manor long remained vested. However, junior branches of the family retained the ancient name and in the town of Lancaster there were in the seventeenth century more than one branch of the family bearing the name of Heysham." - from the "Life of John Heysham, M.D."At this point it is important to provide an important 'however' to this theory. That our family was said to have Norman roots is almost too easy and too predictable. In the class conscious England of the eighteenth and nineteenth century's every family sought such 'aristocratic' roots. A discussion of the medieval history of the village of Heysham notes that

"The local surname [Heysham] appears to have been used by several families, one of them, as already noticed, being tenants of the Prior of Lancaster." - from "The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster" Volume 8 by William Farrer and J. BrownbillSo some of those who bore the Heysham name might have been heirs of the Gernet's while others were not. There are several equally probable ways the family could have acquired the de Heysham name, though there is no way of proving or disproving any of the alternatives.

First, a man born in Heysham, having moved to Lancaster or beyond, might use the appellation to differentiate himself. For example he might be introduced, "This is John. No, not John of Halton, but John of Heysham." This type of descriptor would also commonly be used in court procedures where surnames were lacking. The surname might stick and be passed onto his sons.

Second, an illegitimate child, the result of a union between a serving girl and one of the Gernet boys (or a bastard child of one of the Gernet girls for that matter), might appropriate the de Heysham name, both in pride of the connection and in defiance of a family that would not want this alliance recognized. However, it should also be noted that not all fathers of bastards rejected their children, especially at this early point in history. Many Kings of England set their bastards up as Earls or Barons, giving them everything but their name.

Third, a servant or a man sub-enfeoffed of the Gernet's of Heysham might be referred to, almost as if he were part of the property, as "of Heysham [manor]."

However, to make one final point in defense of the Gernet connection, the use of a 'domain' name like de Heysham by someone not entitled to it, especially in Lancashire very near the bounds of the Gernet manors, could be dangerous. The family would jealously guard their entitlement because any unauthorized use of this domain name could diminish their entitlement, both now and to future generations. This is very like the way a modern corporation protects its trademarks. For example, use the uncapitalized word jeep in a publication and you will hear from Chrysler's lawyers. In 1170, according to the Justicar of England, "every little knight in England had his seal" which protected their domain rights.

In the 12th century, Adam de Gernet de Hessam [that is, "Adam of the Gernet family of the vill of Hessam"], held the Heysham manor by the "tenure of serjeanty" or "service of Cornage."

Def: Serjeanty - A form of landholding under the feudal system, intermediate between tenure by knight-service and tenure in socage. It originated in the assignment of an estate on condition of the performance of a certain duty, other than knight-service. It ranged from service in the kings host, distinguished only by equipment from that of the knight, to petty services not much different than those of a rent-paying tenant or socager. Grand serjeantry was that held directly of the King.Serjeanties included such major duties as acting as the King's Marshal or King's champion, and keeping the jail in Winchester Castle. Minor duties that rated a serjeanty included holding the king's head when he made a rough passage across the Channel, pulling a rope when his vessel landed, counting his chessmen on Christmas day, bringing fuel to his castle, doing his carpentry, finding his potherbs, forging his irons for his ploughs, tending his garden, nursing the hounds gored and injured in the hunt, and serving as veterinary to his sick falcons. The Gernets held the title of King's Forester of Lancashire, the most important serjeanty in the county.

The meaning of serjeant as a household officer is still preserved in the king's serjeants-at-arms.

| The King's Forester

"Foresters and huntsmen occupied an ambiguous position in Angevin England. Some forest officials, including those serving the king, appear to have been keen to broadcast their exercise of office. A deed of Gilbert the forester's near-contemporary, William of Mitcheldean (Glos.), for the Cistercians of Flaxley styled himself regis forestarius . . . At the same time, forest officials were the subject of extensive animosity and widespread abuse . . . against 'the tyranny of foresters' (tyrannis forestariorum). Given the scale of this low regard, it must be significant that foresters and huntsmen figure noticeably as victims of violence in miracle collections and saints' lives." - from "The Murder of Gilbert the Forester" by H.F. Doherty in "The Haskins Society Journal 2011: Studies in Medieval History" edited by William North |

"In England some estates were held on a cornage tenure, to blow a horn in case of an invasion, generally on the Scottish borders. The Barony of Burgh-on-the Sands, in the county of Cumberland, was anciently so held. "Rogerus de Hesam tenet duas carucatus terrae, per servitium sonandi cornu suum guando Rex intrat et exit comitatum Lancastriae."" - from "The British Army: Its Origin, Progress, and Equipment" by James Sibbald David Scott, Sibbald David Scott.

In the feudal era there were a number of "Peculiar Services and Tenures,"

"The following are entries in the "Test de Nevill," a book supposed to have been compiled towards the close of the reign of Edward II. or the beginning of that of Edward III., and consequently to exhibit the services and tenures existing about the beginning of the 12th century: . . . Roger Gernet, by being chief forester. William Gernet, by the service of meeting the king on the borders of the city, with his horse and white rod, and conducting him into and out of the city. William and Benedict de Gersingham [possible Gernet relatives], by the sergeantry of keeping the king's aeries of hawks. Gilbert Fitz Orm, by paying yearly 3d. or some spurs to Benedict Gernet, the heir of Roger de Heton [Heaton or Halton?], in thanage . . . Roger Fitz Vivian [Roger son of Vivian Gernet] holds the sergeantry of Heysham, by blowing the horn before the king at his entrance into and exit from the city of Lancaster. Thomas Gernet, in Heysham, by sounding the horn on meeting the king on his arrival in those parts." - from "Lancashire Folk-Lore," pages 278-280.

| Feudal Tenure

The ultimate source for all English property in the Medieval period was the King, who was known legally as the Lord Paramount. A lord might hold land immediately of another, but mediately of the King. Those who held lands immediately of the King were called his tenants in capite, or tenant in chief. They, in turn, could offer inferior tenures for which they had to pay their superior lord a fine for alienation of the estate. A man who was both lord and tenant was known as a mesne lord. His vassal was called the tenant paravail, because he was supposed to make avail, or profit, of the land. If a tenant had no heir, upon his death the estate went back to his lord. Such a reversion was called an escheat, or escheatment. Tenure was classified as either free or unfree. Unfree, or servile, tenure was generally that of the villein, or serf, who performed manual labor and was a tenant at the will of the lord. The serfs were tied to the land as property of the manor. Free tenure was a means for ensuring the performance of services required by the state. It included, - Knight tenure. The obligation to provide military services, or a particular number of knights, when asked. As a money economy developed, most of these services were commutated into fixed monetary payments. |

What I find most interesting about the orgins of this name is that it developed so early, circa 1050, when the use of surnames was in its infancy. There are several theories about the origin of the Gernet surname, though none of them can be proved. From the conspicuous service of cornage it has been said that,

"the Lords of the Manor of Heysham acquired the surname of Cornet, eventually transformed into Gernet, in which name the manor long remained vested." - from the "Life of John Heysham, M.D."

"See, too, the seal of Roger Gernet, hereditary forester in the the honour of Lancaster, which depicts him on horseback, blowing his hunting horn (Durham, DCM 3.2.4 Ebor 4). Roger Gernet was described in 1212 as holding his property of the king in forestaria (Bk. of Fees, i, 212). In 1226 Roger, his brother Vivian, and one Roger the forester were accused of killing a man because Roger and his men had been contradicted 'concerning the perambulation of the forest in those parts' (quod ipsi oblocuti sunt de perambulacione foreste in partibus illis) (Rot. Litt. Claus., ii, 163b, 166)." - from "The Haskins Society Journal 2011: Studies iin Medieval History" by William NorthThe instrument we understand today as a cornet, a brass trumpet with a slightly smaller bell, was not developed at this time. The cornett was a curved wooden instrument, looking something like an animal's horn, that was fingered like a flute and was known as early at the tenth century. Doug Garnett, another researcher of this family, indicates that the family were also heralds and that the cornett was part of the family coat-of-arms.

"Although I have not been able to find a copy of the original design for the Coat of Arms granted to the early GERNET family of Halton, it is said to have included a representation of the royal hunting horn that was a symbol of their hereditary office. The hunting horn or bugle was probably used as a mark of the family's trade or entitlements and their Coat of Arms was derived from these hallmarks of their royal appointments." - Doug GarnettI haven't seen that in contemporary arms, though much later the Garnett's of Quernmore Park used a buglehorn, similar to that shown below.

I don't find either of these explanations satisfactory because the Gernet name was established before the family gained the office of Forester or began to render the service of cornage.

During the Middle Ages in England gernet was a word which meant pomegranate, the fruit. The original root word was the Latin granum, meaning grain or seed. Granatus meant having many seeds and it was the Romans who called the fruit a granatum and, later, pomegranate, that is, an apple, pome, having many seeds. The scientifict nomenclature for the pomegrante tree is Punica granatum referring to what the Romans believed was the Punic, i.e. Carthaginian, origins of the fruit.

During the Middle Ages in England gernet was a word which meant pomegranate, the fruit. The original root word was the Latin granum, meaning grain or seed. Granatus meant having many seeds and it was the Romans who called the fruit a granatum and, later, pomegranate, that is, an apple, pome, having many seeds. The scientifict nomenclature for the pomegrante tree is Punica granatum referring to what the Romans believed was the Punic, i.e. Carthaginian, origins of the fruit.

Later the word gernet evolved into garnet. The pomegranate plant even became known, for a time, as the garnet-tree and the fruit as the garnet appille, or apple. - from "The Anglian" by Charles Harold Evelyn White.

In French the word was rendered as grenat and in Spanish as grenada, making the automobile of the 1970's a Ford Pomegranate.

One of the armorial symbols of the royal house of Spain was a pomegranate, a play on the city of Granada, the last holdout of the Moors in Spain which the Spanish, under Ferdinand & Isabella, conquered in 1492. At the left is the badge of Catherine of Aragon, daughter of those monarchs, showing the fruit.

The semi-precious stone we call a garnet was then known as a gernet from its resemblance in color and shape to the grains or seeds of the pomegranate. In the following poem, circa 1200 [temp. Edward I], the author compares his mistress to a variety of gems and flowers.

Gernet was also rendered as gernad, garnad, garnard, granat; or plural as garnetes, grenaz, or grenas.Ic hot a burde in a bour, ase beryl so bryght,

Ase saphyr ih selver semely on syght,

Ase jaspe the gentil that lemeth with lyght,

Ase gernet in gold and rubye wel ryght,

Ase onycle he is on y holden on hyght

Ase diamand the dere in day when he is dyht . . .

- from "The History of English Poetry" by Thomas Warton

The English gernet was an adaptation of the Old French grenet (also grenette, grenat, grenate), which, as an adjective, also meant "of a dark red color," probably from the color of the pomegranate's seeds. Note how the French grenet became in England, gernet. This "er" inversion was common and will be significant in our later discussions.

So the name Gernet may have been a nickname, meaning simply red-haired or ruddy complexioned. Applying that to our generation (1) ancestor Ralph de Gernet, who you'll read about below, we have Ralph the Red, which kind of reminds me of the Viking, Erik the Red. I would be more comfortable with this explanation if there were other examples of this use of le gernet as an appelation, as there are for le roux or the English "rufus."

To keep the derivation going, a small bomb thrown by hand is called a grenade because, in the 16th century, soldiers thought the early versions looked like pomegranates and were filled with "seeds," or grains of powder. A company of soldiers trained to handle grenades became known as grenadiers. They were at the forefront of assaults, lobbing their grenades, then forcing their way through the resultant breaches. Grenadiers had to be tall and strong enough to hurl these heavy objects a great distance so as not to harm themselves, or their comrades, in the blast. The use of the grenade declined in the 18th century, but grenadier survived as the name for elite assault troops.

There are a couple of locative explanations for the derivation of Gernet. First, there may be a relationship to the island of Guernsey, one of the Channel Islands. Amongst the names given that island in the Medieval period were Guarnet and Gernet. The surname may thus mean "of Guernsey." Wace, the ancient English poet, referred to Chernerin, a place which may have been Guernsey. The most common translation of Wace's ancient prose is:

"Unt tant coru e tant sigle,Other translaters have evaluated this differently.

En Chernerin sunt arive . . ."

"Other copies read Gernerou or Gerneui; in Peter Langtoft it is Guarnet, in Robert of Brunne Gernet, and in Robert of Gloucester, more correctly, Gernesey, from Geoffreys Garnareia."

- from "Layamons Brut, Or Chronicle of Britain: A Poetical Semi-Saxon Paraphrase of the Brut of Wace" by Layamon, Wace, Society of Antiquaries of London.

Similarly, there is, in the department of Calvados, in the arrondissement of Bayeux [Bayou], in Normandy a village known as Gueron. The family name, as Gueron-et, might show their origins in that place. Note, in the Gernet's of Halton page, that Vivian Gernet was said to be 'of Gueron' by at least one researcher. Gueron is located just south of the town of Bayeux, of which William I's half-brother, Odo, was the Bishop. Its lords were known as the Seigneurs de Gueron. Turstin de Gueron was listed in the Dives list of those knights that accompanied William the Conqueror on his invasion of England in 1066.

"Gueron: Calvados, arr. and cant. Bayeux.Def: Terra Vavassoria - The fief or land of a vavasour, a free man, not necessarily a vassal, from whom military service was due. Also as a knight of only middle rank.

In 1086 Turstin de Giron or Girunde was an under-tenant of Odo biship of Beyeux in Buckinghamshire and Kent. In the Bayeux Inquest of 1133 Gueron occurs as a 'vavassoria' of the bishop of Bayeux." - from "The Origins of Some Anglo-Norman Families" edited by Charles Travis Clay and David Charles Douglas

There is an Ascheter de Gueron listed in the Index Personarum et Locorum of the "Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum: The ACTA of William I 1066-1087." Is Ascheter possibly a profession vice a given name? That is, as in escheat, when an estate fell into the hands of the lord or the state for want of an heir. Spelling variations include Guerrin, Guerren, Guerin, Guerinne, Guerrein, Guereon, Gerin, Garin, Le Guerin, Guerenne, Guerry, Le Guerinne, De Guerin, De Guerrin, and Du Duerin. Guillaume Guerin of Normandy settled in Quebec in 1704.

Doug Garnett feels, after extensive research, that the family name was actually of archaic French origin. The most plausible theory, according to him, being that the family surname evolved from the old French word gernetier, meaning grain-keeper, perhaps indicating an early occupation or a social position, as in superintendent of the grain reserves. This word actually began as grenetier, as is described in the following.

Doug Garnett feels, after extensive research, that the family name was actually of archaic French origin. The most plausible theory, according to him, being that the family surname evolved from the old French word gernetier, meaning grain-keeper, perhaps indicating an early occupation or a social position, as in superintendent of the grain reserves. This word actually began as grenetier, as is described in the following.

"greniers - royal salt warehouse. In most of France, the king held a wholesale monopoly of the sale of salt. The salt tax monopolists (independent contractros, i.e. tax farmers) had to bring their salt to a royal warehouse, where a royal official, the grenetier, registered it and oversaw its later distribution to merchants. The tax farmers collected, on behalf of the king, a fixed amount on every muid of salt registered by the grenetier. The grenetier also served as the judge in the first instance of all small-scale lawsuits related to the salt tax. Each warehouse also had a controller, to check on the grenetier, and an offical measurer of salt. All these offices were venal [open to bribery; mercenary]." - from "The State in Early Modern France."The reference to the salt tax is, for our purposes, anachronistic since it was not established until the 13th century. However, I have seen references to both "le grenetier du grenier a sel," or grenetier of the salt warehouse, and to "le grenetier des graines," or grenetier of the grain warehouse, so the word may apply to both the warehousing of salt and grain. Grenier referred to a warehouse, barn or granary. In Middle English this became gerner, or storeroom. Again, the root word is the Latin granum, as it was for gernet. The French word grenetier was transposed when it came into England, both by swapping the "re" for "er," and Anglicizing the suffix.

"gerneter n. Also garneter, garnter. [OF grenetier] One who has charge of a granary, also, a surname; gerneteres man, a servant assisting in a granary . . . Close R. Edw. I 451: William Gerneter. (1318) Pat. R. Edw. II 285: Alexander Gernetersman. (1322) . . . " - from the "Middle English Dictionary"The d'Estouteville's, an important Norman family mentioned below, were at one time "du grenetier de Rouen" - from "Chronique du Mont-Saint-Michel (1343-1468)" by Simeon Luce. The great de Guise family also were grenetier. This could be a lucrative post and, not surprisingly, was often hereditary. Grenetier became a surname of course. There was a Jean le Grenetier, of Paris, in the 15th century and today Jean Roch Grenetier lives in Milwaukee, Benjamion Grenetier is a French du- and tri-athlete, while Benoit Grenetier, a vintner, lives in the Loire region of France. Lazare de Baif was the Abbot of Charroux and Grenetier, probably in Anjou or the region near Paris. So, was Grenetier also a town? I haven't resolved this point yet. There is, in Fecamp, a Rue Grenier a Sel, street of the salt warehouse.

In England the occupational title of gerneter was current as late as 1348 and that of garneter to 1603, as seen in Shakespeare's use of it in his Funeral piece for Elizabeth I. Supporting the supposition above, in the Fine Rolls of Henry III, Sir Roger Gernet of Halton, the King's Forester, was, in a dispute with the lepers of St. Leonards, referred to as Roger Gerneter. There is also a reference to a "William de Gerneter 1296" in "A Dictionary of English Surnames." A little later, in 1325, a Robert le Gerneter was a witness to document of the Petre family of Ingatestone Hall, in Essex. In a Latin text we have a reference to a Gerneter family in Durham,

". . . rendo sibi et haeredibus suis, de Willelmo Gerneter, unum messuagium, viginti et novem acras terrae, et unam acram prati et dimidiam, cum pertinentiis, in Norton', quae de nobis tenentur in capite, eaque in- . . ." - from the "Registrum Palatinum Dunelmense: The Register of Richard de Kellawe, Lord Palantine and Bishop of Durham" by Thomas Duffus Hardy, Richard de KellaweAlso in Durham,

"Of the Durham merchants, one of them in a moderate way of business, two made two consignments each. Robert le Gerneter exported 8 sacks of wool and 200 wool-fells and 13 stones of wool and a last of hides." - from "Archaeologia Aeliana"There was also a John le Gerneter and a "Ricardus le Gerneter essoniator abbatis de Fontibus optulit se iiij. die versus . . ." in York - from the Curia Regis. Jacobus and Ed. Garneter were litsters, or dyers, of York during the reigns of Henry VI and Edward IV.

I find the explanation above very persuasive, but that offered next is also. The English and Welsh Surname Dictionary has this to say about the issue:

"Garnett, Garnett - Bapt. 'the son of Garnet,' if such a personal name existed, but more probably 'the son of Guarin' [a given name of the period]. Although I have no absolute proof to adduce, I cannot hesitate to assert that this is the O.F. Guarinot (a diminutive in ot of the very popular Guarin), just as Warnett is Warinot (a diminutive in ot of Warin), the English dress of the same name (v. Wareing and Warinot). Assuredly it is a font-name, or the pet form of a font-name. An inspeximus [royal grant] of the charter of the manor of Ulverton, 10 Henry IV* [1409], is witnessed among others by 'Garnet our Forestor' (West's Ant. of Furness, p. 34)."In the French language, unlike English, all nouns have gender, the suffixes -ot and -et denoting the masculine diminutive. So a young man, whose father's name was Guarin, might become known as Guarin-ot or Guarin-et, that is, "little" Guarin, just as a small lance is a lancet. Note that Ralph Gernet, below, was also known as Radolphus Guernet. The given name is apparently Germanic/Frankish in origin. Variations of Guarin include Guerin, Garin, Guarinet, Guarinus, Guerinnet, Warin, Warinus, Warren and Warrenus. Common given names in Normandy include "Garin, Gerrin, Guerin, Guerinaud, Guerineau, Guerinet, Guerinon, Guerinot" - from "Surnames in Normandy."

The date of the charter for "Garnet our Forester," above, can not be right. The Gernet family lost the hereditary title to the Earl of Lancaster, a son of Henry III, who had revoked it in 1280. If we assume the above should actually be '10 Henry III,' that would be 1226, or when Roger Gernet was still Forestor.

I have an undated charter of the chapter house of St. Evroul in which Humphrey de Merestona gave all his land in the demesne of Danblainville. This was witnessed by a Guarnerius. Another document, of 1092, was witnessed by Gislebertus Guarnerii filius.

I have an undated charter of the chapter house of St. Evroul in which Humphrey de Merestona gave all his land in the demesne of Danblainville. This was witnessed by a Guarnerius. Another document, of 1092, was witnessed by Gislebertus Guarnerii filius.

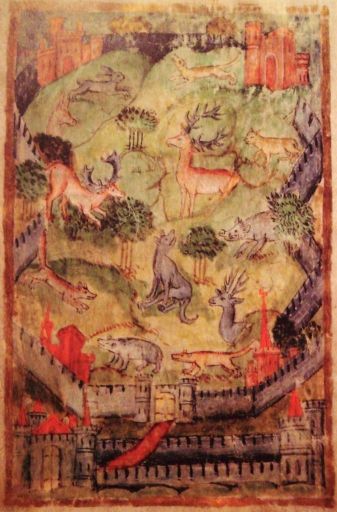

Kate Monk's Onomastikon, or dictionary of names, describes the given name Warin [the English of Guarin] as a "tribal name" of Norman or Germanic origin, "or the placename La Varenne, 'game-park'." The Wiktionary refers to two different Norman surnames, both rendered Warren, "one from a Germanic given name war(in) "guard", another from a place La Varenne "the game park" in Normandy." The name of the town of La Varenne itself was derived from the Old French garenne, which meant game park, or reserve, or perhaps most explicitly, game fencing. The town of Clichy, northwest of Paris, was known as Clichy-la-Garenne, Clichy the Warren, for its role as a one-time game preserve. A garennier, or in England warrenier, managed a game park. This seems to lead us back to the Gernet occupation of forester. Could the family have been foresters prior to the Conquest? That is, were they garenniers vice grenetiers? The Gernet name would then derive from garennier-et, or Garin-et, the son of the game keeper. Interesting, but if the Gernets brought their occupation with them from Normandy, they pursued it only in Lancashire. I've found no records of the Essex or Hampshire lines being foresters or game keepers.

Note that the Dukes of Normandy had established royal forests and forest laws in the 9th and 10th centuries based on the Carolingian model. The forest of Eu, north of Fecamp on the Norman coast, was a ducal hunting preserve as was the forest of Arques.

PronunciationThe name Gernet may have been pronounced like the gem, garnet, with the accent on the first syllable (GER-net), or like the name, Garnett, with the accent on the second (ger-NET). That reminds me of a situation here in San Diego. The city fathers named several sets of streets in the city, in alphabetical order, after trees (i.e., Ash, Beech, Cedar, Date), birds, authors, and, in the Pacific Beach area, gemstones. Garnet street, then, should be pronounced like the gem, but locals insist on putting the accent on the second syllable, leading to the rhyming complaint, "Its garnet, darn it!"

A modern looking at the Gernet name might assume that its first syllable was prounounced like the animal sound, 'grr.' However, according to Bill Bryson in "The Mother Tongue," before the time of Shakespeare there occurred what he called the Great Vowel shift in which most vowel sounds shifted forward and upward in the mouth. Because of this, what we read as 'er' they pronounced as 'ar;' person was parson, heard was hard, and defer was defar. How do we know this? Apparently researchers looked at the rhymes used by poets of this earlier period and how words were misspelled in letters. If this was so, then Gernet was prounounced as Garnet. Note that late in the 14th century Joan Gernet, the heiress of Halton manor, was referred to as Joan Garnet and by the 16th century almost all of the family were known by that name.

As a "French" name, was Gernet pronounced like ger-NAY or gar-NAY? By the way, I've always liked the German language because you pronounce everything just as written, while only the French would pronounce printemps as pron-tom. Gernay/Gernaey/Gernai is a family name in Belgium. Hugh de Gournay [Gournai], Seigneur of Gournay-en-Brie, in Normandy, was one of the Conqueror's companions. Grenay is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department of France.

Note also that several references on this page indicate that the French Guarin and English Warren were probably pronounced the same way. If so, the surname may have been "War-nay." But, my guess is that the English, in their peculiar fashion, would have pronounced this French name in an English way, just as the French Beuchamp is somehow transfigured into the English "Bee-chum."

A variation of Gernet, limited to Hampshire, was the use of the spellings Kernet and Chernet. What does that say about pronunciation? I would guess that in this case the first two letters of Chernet were prounounced as the tch of cherry vice the sh of cherie. I was pleased to see this point substantiated by Bill Bryon in "The Mother Tongue." He noted that French words adopted before the 17th century were Anglicized while those adopted afterwards were not. "Thus older ch- words have developed a distinct "tch" sounds as in change, charge and chimney, while the newer words retain the softer "sh" sound of champagne, chevron, chivalry, and chaperone."

The Gernet Family & the ConquestDuke William's invasion of England was supported not only by his Norman vassals, but by a wide variety of lords, knights, and freebooters from throughout northwestern Europe who hoped to gain both booty and lands. The Gernet's came to England at about this time and became part of the Norman overclass in England. Interestingly, at least to me, the Montague's, my wife's family, also trace their origins to Normandy and a Drogo de Monte-acuto, who was born around 1040. See the Montague web page for more about this.

There have been many lists compiled of the men who accompanied William on his conquest, but all are in one way or another suspect.

- The most accurate is the Bayeux tapestry, commissioned by William not long after the victory. For those named, on the Norman side, see William's Battle Force.

- The Battle Abbey Roll, named after the abbey founded by the King at Hastings, may have been an accurate list at some point, but it has been spoiled by many additions by more modern family's trying to improve their genealogies.

- The Dives Roll was compiled in the 19th century based on a memorial at the Dives-sur-Mer church in Calvados, Basse-Normandie, that supposedly commemorated the men who followed William.

- The Falaise Roll was compiled from the works of Orderic Vitalis, Wace, the Bayeux tapestry and other researchers.

- The Domesday Book also cites some of these warriors.

- Another source available online is The Conqueror and His Companions, by J.R. Planche, Somerset Herald. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1874. This is one of the most fully researched and readable compilations.

The following is an attempt to identify an ancestor in the generation of the Conqueror, in France, using the naming conventions discussed earlier.

(-1) Guerin or Du Grenetier des Graines (c1020)A possible/theoretical French ancestor of both the French Grenets and the English Gernets. A father, named Guerin, or occupationally du Grenetier des graines. He would be a member of the petty nobility and, based on later affiliations, a vassal or client of the Montgomery family.

His supposed sons, William Grenet and Ricard Gernet, were newcomers to Normandy circa 1088 when they were enfeoffed out of ducal properties around Fecamp by Robert Curthose, the eldest son of the Conqueror. They may have also held lands in England circa 1094 as William Chernet of Hampshire and Richard Gernet of Essex. If newcomers, then where did their father, Guerin, come from? My best guess at this point is Chartres, to the east of Normandy, in the old county of Blois. There was a family of Gernets living there from at least 1096 to the 17th century. They appear to have been merchants or tradesmen of some consequence. Might their fortune have been based upon a patronage job as du grenetier de Chartres in the 11th century?

There is a reference in the "Battle Abbey Roll" to a companion of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings known only as "Greuet; no doubt for Gernet, a well known Lancashire house." A foot note advises: "This transposition of the letter "r" is by no means uncommon. Gernon, for instance, is several times given as Grenon in Domesday." The book is surprisingly quiet on the substitution of "u" for "n." Another online researcher helpfully notes that when reviewing lists that "have been copied, recopied and miscopied several times" errors creep in. "Handwritten "u's" and "n's" tend to get confused as might "e's" and "a's."" So perhaps Greuet=Grenet=Gernet.

I don't see any Greuet at the linked article above, though it is in "The Battle Abbey Roll" by the Duchess of Cleveland. I do see Ascelin de Gournay [later Gurney], Hugh de Gournay, Robert Guernon, Sire de Montifiquet [later Mountfitchet], and Guillaume [William] de Warren[e].

| The Battle Abbey Roll

|

The Abbey Roll goes on to say, "The name [Gernet] appears in the Norman Exchequer Rolls of the twelth century. "Guillaume de Carnet" is entered on the Dives Roll . . ."

| Dives Roll

The Dives Roll was compiled in 1866 by Leopold Delisle and included 485 "Companions of William the Conqueror at the Conquest of England in 1066." This was subsequently inscribed on a memorial erected in the church at Dives-sur-Mer where William prayed before leaving France. "In many instances, the [Dives] list seems to be taken from [the] Domesday Book, but as the Duchess of Cleveland said, it is to be regretted that he [the Dives Roll compiler] has in no case cited an authority or given a reference." Delisle was a genuine scholar, but the roll is considered to be an unreliable source for William's companions. Some go as far to call it an outright fabrication. Again, however, the issue is, which entries are true and which are false? Names of interest on the list include, Ansger de Montaigu |

On the Falaise roll there is a Hugue de Gournay and a Hugue de Gournay "le Jeune," as well as a Guillaume de Warren. Remember that Warren is a variation on Guarin, i.e. Guarin-et=Guernet=Gernet.

| Falaise Roll

The Falaise Roll is a list of 315 names engraved on the bronze memorial erected in 1931 in the chapel of the castle of Falaise in Normandy. These individuals were chosen because of the probability of their having fought in the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Names of interest on the list include, Ansger de Montaigu |

The scenario would be that a man called Greuet or Guillaume de Carnet took part in some fashion in the invasion of England, perhaps under the banner of Roger Montgomery. The Montgomeries were richly rewarded by the Conqueror for their service and they, in turn, would have rewarded their own retinues. The earliest lands available for patronage were in the south and east of England where the Gernet family first appears as land-owners. Later, when the north of England was subdued, at least one member of the family was granted land in what would become Lancashire.

Members of the Gernet/Grenet family continued to live on both sides of the channel. See Grenet Family of France and Gernet Family of England.