|

The Hissem-Montague Family |  |

|

The Hissem-Montague Family |  |

We have written previously that our Heesom/Hissem forebears may have initially settled in East Yorkshire. This region, pierced deeply by the Humber estuary, was a favored dropping off point for both the Bell Beakers and the Celts during the Bronze and Iron Ages. If so, then the next phases of our history, the Anglo-Saxon invasion and, later, the onslaught of the Vikings, may have provided the push to move them westward, into Lancashire. It was there that I believe we received our surname.

Britain After the RomansIn the immediate aftermath of the Roman withdrawal the province of Britannia began to break apart. Powerful men set themselves up in strong places, declared their lands kingdoms and themselves kings, and began to wage petty wars. The area around Hessam fell under the control of the Celtic Kingdom of Rheged whose center of power was to the north, around Carlisle in present day Cumbria. This kingdom further splintered into the kingdoms of North and South Rheged when two sons squabbled over their inheritance.

| Historical Timeline: England, the Celtic Kingdoms, 410-685 AD

Celtic kings of Northern Britain: Northern Britain, at York: |

The disorders that followed the breakup of Britain resulted in a wholesale depopulation of the island. At the same time the good weather of the Roman Optimum came to an end and the colder and wetter environment resulted in famine and a movement towards the south. The towns that remained, like London, Londinium, shrank precipitously and became too small for the Roman walls that had previously protected them. Trade disappeared and ships were left to rot at their piers. Constant warfare and cycles of famine and disease became the expectation of the common man. These were indeed the Dark Ages.

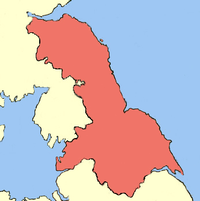

| Deywr: Celtic Kingdom in East Yorkshire

During the withdrawal of Roman administration from Britain and for a century and-a-half afterwards, Deywr formed part of the territory that came to be known as the 'Kingdom of Northern Britain'. In effect this was the Late Roman province of Britannia Secunda, which encompassed all the land north of the Humber and south of Hadrian's Wall. Tradition, perhaps a little unreliably, says that it was governed by Coel Hen in the last days of the Roman period of the Diocese of the Britains and the first decade of independent British administration. After that it became an hereditary possession, and in the Celtic tradition it was slowly divided and sub-divided. The region known as Deywr remained part of the kingdom of Ebrauc (it was apparently never a kingdom in its own right). This south-eastern section of Northern Britain was ruled from the Roman city of Eboracum, or Ebrauc to the Britons (modern York). Deywr's original territorial boundaries are probably mirrored in the modern county boundaries of East Yorkshire. It is likely that the region regarded Petuaria (modern Brough, possibly the tribal centre of the Parisi prior to Roman rule) as its local capital, until this lost its importance in the mid-fourth century, perhaps because the harbour had silted up. Thereafter, the region's main military post moved to Malton. In the early 5th century AD an Angle King, Saebald, the son of Swebdaeg, led his people into Deywr to settle as laeti, mercenaries in the Roman tradition. In 559 his descendants founded the independant Anglian kingdom of Deira. |

In addition to internal disorders the Romanized Celts of Britain also suffered from attacks by their wild cousins out of Scotland and Ireland. In 446 the Britons asked again for aid from Rome, but the Emperor did not respond. In about 450 the Britons called on mercenaries from Germany to defend them. Of this the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles reported:

"Mauricius and Valentinian obtained the Kingdom and reigned seven years. In their days Hengest and Horsa, invited by Vortigern, King of the Britons, came to Britain at a place called Ebbsfleet at first to help the Britons, but later they fought against them. The king ordered them to fight against the Picts, and so they did and had victory wherever they came. They then sent to Angeln; ordered them to send them more aid and to be told of the worthlessness of the Britons and of the excellence of the land. They sent them more aid. These men came from three nations of Germany: from the Old Saxons, from the Angles, from the Jutes."So commenced the adventus Saxonum, the Anglo-Saxon invasion of England.

There are disagreements about what an Anglo-Saxon conquest might have looked like. It is unlikely that the Celts were all swept from their land and forced to take refuge in Wales and Cornwall. The German advance and settlement was slow, if, in the end, inexorable; Rheged, where modern-day Heysham lies, did not finally fall until the end of the 7th century. Most of the Celtic residents, the peasants, were probably absorbed into the Saxon community rather than killed or driven off. Their culture, language and arts, however, would have rapidly withered in the new society.

| Historical Timeline: The Roman Withdrawal

In 476 AD the Western Roman Empire came to an end with the murder of the last Emperor of the West, Romulus Augustus. The Eastern Roman Empire continued for another thousand years, centered on the imperial capital, the impregnable city of Constantinople. |

The legend of King Arthur arose from events in this period. His story is based on a Celtic warlord, supposedly the son of the Roman Ambrosius Aurelianus, who, in about 500, defeated a Saxon army at the battle of Mount Badon, creating a short period of peace, fondly remembered as a golden age, before the invasion regathered force. The 6th century Welsh poet Taliesin, the bard of King Urien of Rheged, referred to

"the battle of Badon with Arthur, chief giver of feasts, with his tall blades red from the battle which all men remember."Some commentators, perhaps too romantically, have linked Sarmatian troops in Roman service to the Arthur legend. One of those possible links was the Sarmatian altar which, supposedly, was a tightly bound bundle of sticks, into which was thrust a sword, that is, a kind of sword in the stone. This probably does not deserve further comment.

| The Kingdom of Rheged

Rheged's great king was Urien, son of Cynfarch, who gained a number of victories over the encroaching Angles, at one point driving them back to the island of Lindisfarne. His exploits were recorded in the Historia Brittonum of Nennius and the poems of Taliesin. In the Llyfr Taliesin, the book of Taliesin, Urien was referred to as gwledig, a title conferred on families of Roman descent who acted as commanders of native defense forces. He was murdered in 590 by a rival ruler. Nennius wrote, "Four kings fought against them [the kings of the Bernicians], Urien and Rhydderch Hen and Gwallawg and Morcant. Theodoric [the son of Ida] fought vigorously against Urien and his sons. During that time, sometimes the enemy, sometimes the Cymry were victorious and Urien blockaded them for three days and three nights in the island of Metcaud [Lindisfarne]. But during this campaign Urien was assassinated by the instigation of Morcant, from jealousy, because his military skill and generalship surpassed that of all other kings." During Urien's reign his cousin, Llywarch Hen, ruled in the south, perhaps from the old Roman fortress of Ribchester. After Urien's death he was driven into Wales by princely infighting. Urien's son was Owain who continued to fight the long defeat. Upon his death the kingdom finally succombed. |

Our ancestors in this era, drifting south into Lancashire from their place along the Wall or driven west from Yorkshire, kept their heads down and quietly farmed their small plots, doing their best to avoid or placate both the raiding Angle's and the grasping Celtic lords. I don't think they were members of the raiding parties; ancestors tend to be men who raise families, not a ruckus. By the way, the village of Heysham was at this time a very isolated place, surrounded by marshy ground, hazardous to cross at high tide; a good place for staying out of the way.

As if things weren't ugly enough, an outbreak of plague was recorded amongst the British population in the middle of the 6th century, a mortalitas magna.

The Anglo-Saxons of northern Germany and Denmark would be mainly haplogroup R1b, I1, and R1a. G2a is notably sparse in northern Germany, though much higher than in England (3.5% versus 1.5%). Denmark is just 2.5%.

"Germanic people brought a whole new set of paternal lineages with them, namely I1, I2a2a-Z161, R1a (L664 and Z284), R1b-U106, and to a lower extent Q1a. Those haplogroups now make up over half of all male lineages in England and Lowland Scotland."

"Nevertheless, an east-west gradient does exist between Gaulish Celtic or Roman lineages (both R1b-U152) in the east and Insular Celtic (R1b-L21) in the west. Cornwall and Wales have hardly any U152 at all, but boast respectively 40% and 65% of R1b-L21. If we exclude Germanic lineages, Ireland is almost purely Insular Celtic, L21 superseding U152 by a ratio to 50 to 1. The highest frequencies of Gaulish and Roman U152 are observed, unsurprisingly, closest to the continent, in southeast England and East Anglia." - from eupedia.com

The middle and east of Britain was generally settled by the Angles while south Britain was conquered largely by the Saxons. England derives its name from Angle-Land and Anglecynn, or Angle-kin, was the origin of the word English.

To the east of the Celtic kingdom of Rheged, where Hessam lay, were Bernicia and Deira. Originally Celtic, they were conquered early by the Angles.

To the east of the Celtic kingdom of Rheged, where Hessam lay, were Bernicia and Deira. Originally Celtic, they were conquered early by the Angles.

The Angles had begun their invasion of the north in about 450, colonising the Yorkshire Wolds, just north of the Humber estuary. This region, now East Yorkshire, became the kingdom of Deira. As the Angles pushed further north along the North Sea coast, they founded the kingdom of Bernicia.

The first Anglian King of Bernicia was Ida, who obtained the throne in 547, conquering the British stronghold at Bamburgh. The Britons of Rheged, led by their warrior-king, Urien, fought back, driving the Angles to the sea, but Urien was assassinated by a rival Celtic ruler and Rheged's armies fell back into the west. The area around Hessam, in South Rheged, became a contested region, overrun by the armies of Northumbria as they pushed west and by the Celtic armies of Rheged and Gwynedd, in northern Wales, as they vainly resisted the onslaught.

Ida's grandson, Aethelfrith, decisively defeated a combined British force and the Celts had to recognize Bernician hegemony in the north. Athelfrith seized the crown of Deira, and in about 604 united the two Anglian kingdoms to create the kingdom of Northumbria, that is, the kingdom north of the Humber river. In 615 Athelfrith defeated the Welsh in Chester and seized South Rheged. There was a royal marriage in about 638 between Aethelfrith's son, later King, Oswald, Oswiu, and Rhianmellt, a princess of Rheged, which may mean this final conquest was a peaceful one.

See Anglo-Saxon and Viking Northumbria for more.

| Historical Timeline: England, the Saxon Heptarchy, 547-866 AD

Northumbria had reached its peak, but in 642 King Penda of Mercia invaded and killed Oswald at the battle of Maserfield, establishing Mercia, the middle kingdom, as the dominant force for the next 150 years. After about 800 AD the kingdom of Wessex gained the ascendancy, but none of these rulers were strong enough to unify the country. |

In the early 7th century, after South Rheged had been annexed into the kingdom of Northumbria, a tribe of Angles settled along the coast of Morecombe Bay, in the west of Lancashire on the Irish Sea, and established, or took possession of, a village there, on a small promontory overlooking the sea, now called Heysham Head.

In the early 7th century, after South Rheged had been annexed into the kingdom of Northumbria, a tribe of Angles settled along the coast of Morecombe Bay, in the west of Lancashire on the Irish Sea, and established, or took possession of, a village there, on a small promontory overlooking the sea, now called Heysham Head.

As the fortunes of the many Celtic and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms waxed and waned, their borders, and their wars, lapped over the village of Hessam. The affect of this constant state of war on the populace can easily be imagined.

Everyday Life in Anglo-Saxon EnglandDuring the early years of the invasion the native population attempted to maintain the vestiges of Roman life, but this was only marginally successful, and then only in the larger cathedral towns. The legend of King Arthur, and his attempts to recreate a mythic period, dates from this time. In northern England the Roman gloss had always been thin and Roman ways quickly disappeared. For the peasant, it probably mattered little whether his lord was Roman, Celt or Saxon, as long as he was left alone.

The Germanic tribes that invaded Britain had, in the beginning, been relatively egalitarian. In the pre-Norman period class structure was broken down into two basic groups, the upper class eorls, or thanes, and the lower class ceorls (churls). The division between the two was strictly in terms of land owned. A man could only be a thane if he owned at least five "hides" of land. Aside from the ownership of land, a ceorl might actually be a richer man than a thane.

Def: The Hide - Also known as a Carucate to the Danes, or more simply a plowland, this was a measure of land; that amount required to provide a living for one free family and its dependents. This was further defined as that which could be tilled by one plough and a team of oxen in one year. Generally equivalent to 100 acres.Below the thanes and ceorls were the slaves. Slavery was one of the biggest commercial enterprises of the Dark Ages, as it had been during the Roman period, and much depended on this involuntary labor force. War was the most frequent source of slaves. Note that slavery was not ethnically based. A Saxon could as easily be a slave as a Celt, and a Celt might have Celtish slaves.

| Slavery in England

Slavery was rare during the early history of man. A hunter-gatherer population of the Paleolithic did not possess the economic surplus or population density to make it viable. The situation changed during the economic boom of the Neolithic. Almost every ancient civilization practiced slavery. These slaves were often obtained through warfare, but peasants could fall into slavery due to debt or as punishment for crime. To a great extent the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire were financed by the sale of slaves obtained during their territorial expansion. Britons had been sold overseas as slaves before the conquest and the practice continued afterwards. St. Patrick was sold into slavery, in Ireland, in the early 5th century. Slavery was a big business with almost a quarter of the population of ancient Rome being slaves, acting as laborers, prostitutes and gladiators. Interestingly, slaves also owned their own slaves. A document found in London, dated to circa 75-125 AD, concerns the sale of a woman from Gaul to a slave by the name of Vegetus, who was himself the slave of a senior slave named Iucundus. Slavery continued to be practiced following the collapse of Roman rule in Britain. The trade particularly picked up after the Viking invasions in the 9th century with major markets at Chester and Bristol supplied by Danish, Mercian, and Welsh raiding of one another's borderlands. At the time of the Norman Conquest in the 11th century nearly 10% of the English population were slaves. William the Conqueror introduced a law preventing the sale of slaves overseas, but the practice continued within the country. By about 1200, however, slavery in the British Isles had become non-existent, perhaps because serfdom was a cheaper and more effective method of obtaining labor; you didn't have to feed a serf. In North America the native Indians had practiced slavery of their own people and of other tribes, African slavery was introduced into North America and the Caribbean by the Spanish, Dutch and English in the 17th century due to the scarcity of labor to support their new plantations. Slavery already existed in India where the East India Company was rapidly establishing its control during the 18th century. England was, however, the first nation to take the moral issue of slavery seriously and outlawed it throughout its possessions in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 and the Indian Slavery Act of 1843. An active anti-slavery patrol was subsequently maintained by the Royal Navy. Under pressure from the Abolitionist movement the American Navy began an anti-slavery patrol in 1819, but did not maintain an constant presence on the African coast until the 1840's. While rather late in the 20th century the last nation declared slavery illegal, it still exists throughout large swathes of the world. According to some sources, there are more slaves today than in any time in history. Today slavery is rarely called by its real name. Political prisoners, dissidents, and ethnic minorities are confined to re-education camps that look little different from slave plantations. The line between slave and free is purposefully confused by advocates and the fifth column so that prisons look like slavery, and slavery looks like redemption. |

In the countryside the vast majority of the people lived by farming. The ceorls worked co-operatively, sharing the expense of a team of oxen to plough the large common fields in narrow strips that were shared out alternately so that each farmer had an equal share of good and bad land. Later in history this land became consolidated into large estates by the wealthier eorls. During this later period ceorls worked the land in return for services or produce, or they might work the lord's land a given number of days per year.

This was non-cash economy. Everything that a man could not produce himself was procured through barter, either of the products he produced or of his labor. Some money was minted, and ancient and foreign coins were long used, some from as far away as Byzantium, but their circulation was very limited.

The lifestyle was basic. Even the great lords lived only in wooden halls surrounded by palisades. The peasants lived in one-room huts and subsisted on broth with chopped meat, oat and barley potages, porridge, ale, mead and bread. Communal living was accepted as the norm and no one, except perhaps a King, had much privacy.

The villages were extremely isolated. A cluster of rude houses would be surrounded by a fence, and its land by another outer fence. Beyond that were miles and miles of thick forest and heath, empty and wild, where men would venture by day to herd their pigs or gather logs for winter, but would not willingly spend the night for fear of wolves and things unnamable. Tracks for ponies led through the dense wilderness to other villages, winding among the thickets and marshy places and fording the streams. Men had no conception of maps, no mental image of the shape of their country, or of the relative positions of any of the places within it. If a man was swept away in a war he might never find his way home again.

Religion Religion

The early Anglo-Saxon settlers had been pagans, worshipping the Germanic gods, including Wotan, Thor and Loki. However, by around 600 AD they were being rapidly Christianized, first by Saint Columba, a Celtic monk of the Irish Church, and later by Saint Augustine, a Prior of the Church of Rome. The promise of a golden afterlife to men whose current condition was so precarious was compelling. |

After the unification of England under the Wessex dynasty, the country entered a period of considerable population growth and corresponding economic expansion. More land was put under cultivation, while heavier farming and improved techniques produced a surplus of foodstuffs for trade. Market centers were able to benefit from this and from expanded international trade in luxury goods.

In the north Northumbria was now an earldom ruled by a powerful Saxon family who owed their allegiance to the house of Wessex, but central control from the capital at Winchester was weak and the Earls most often acted as independent lords.

Pre-Conquest Lancashire was a frontier zone with uncertain borders and ever-present instability and insecurity. Until the late 11th century much of Cumberland and north Westmorland was under Scottish overlordship.

The village of Hessam remained on the margins of these great events. The people had a meager existence, living in homes of wood and turf, and eking out a bare subsistence from the sea.

Law & Order in the Anglo-Saxon EraThe Saxons brought tribal customs with them to England, including their system of policing, the keeping of order, and abiding by laws. The members of each settlement were held responsible for their own conduct and that of their families and neighbors. If someone broke the law, he had to reckon with the members of his local community. Each householder was therefore a police officer.

A group of ten families, called a tything, elected a tythingman. He, and nine other tythingmen, reported to the hundredman. This hundredman was responsible for both 100 families and the geographical area occupied by them, which was called a Hundred. A number of Hundreds was organized into a Shire, though the precise number of Hundreds in a Shire varied across the country.

In this early society it was the responsibility of the tythingman to get the villagers to behave properly towards each other, to detect any crimes committed and to bring those responsible, through him and the hundredman, to the Shire Reeve or Sheriff. If a community failed to do this, a fine was imposed on it, and each member was responsible for paying it.

The Anglo-Saxons also brought the jury system to England. This mirrored the administrative system with the villagers being ultimately responsible for justice, even if they met under the guidance of a judge. On the continent a different system developed, based on the Roman model, in which a judge, or a panel of judges, as the representative of the state, was the arbiter of justice and the law.

When the land became settled under one king, he promised them, in return for their conduct, a state of peaceful security throughout the kingdom. This was called, and still is, the King's Peace, or simply, the Peace. So today a person may be taken to court for "causing a breach of the Peace." Linked to this social responsibility was the obligation on all men over 12 years of age to join in and pursue someone who had committed a felony. This was called "the hue and cry," and to raise it, was to stir the community to action.

The Shire & the ReeveThe hundredman was the local Reeve, from the Old English gerefa or chief. He was an elected official who was both policeman and judge.

When groupings of Hundreds banded together they formed a Shire, from the Old English scir, an administrative unit, like a county. The Reeve of the county, or shire, was the Shire Reeve, or Sheriff, an official appointed by the King. This Sheriff was originally an entire local government unto himself, exercising judicial authority and collecting taxes. To be appointed Sheriff was considered a significant, if not costly honor. If the people of the county did not pay the full amount of their taxes and fines, the Sheriff had to make up the difference out of his own pocket. In time, the Sheriff was relieved of some of these responsibilities and only had to be concerned with the maintenance of law and order.

When the hue and cry was raised, the Shire-reeve would accord the group with the position of "posse comitatus", the power of the county, and with the help of the tythingmen the posse would bring the felon to justice.

The HundredsGeographic size varied, but the basis for drawing up the Hundreds of a county was pretty much the same everywhere. It was an area that comprised 10 tythings, or one hundred families (or one hundred hides). They were judicial, military, and taxation units that emerged in the Anglo-Saxon period.

This ancient division is not found in every county. The four extreme northern counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Durham, and Northumberland were broken up into wards. On the eastern side of England, the equivalent of a hundred is the wapentake, a term which the Danes brought with them. Wapentakes are found in Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland, and Yorkshire.

By the way, Yorkshire also has its 'ridings', North, East, and West. Riding is derived from an Old English word meaning third part, which explains why there never has been a 'south' riding.

Lancashire had six hundreds: Lonsdale, Amounderness, Leyland, Blackburn, West Derby and Salford. For comparison, Cornwall had nine hundreds, Essex had twenty, and Norfolk had thirty-three. The larger number of hundreds reflect the larger number of people per square mile and the greater fertility of the land.

Area of the Lancashire hundreds:

Amounderness: roughly North of Preston to South of Lancaster, including the parishes of Preston, part of Lancaster, and Garstang.North and South Lonsdale Hundred:

Blackburn: east of Preston to Yorkshire West Riding

Leyland: south of Preston to Standish, including the parish of Eccleston.

Lonsdale North: Barrow-in-Furness, Cartmel, part of Lancaster, Heysham, Halton, Bolton-le-Sands, and Ulverston.

Lonsdale South: Lancaster, North Lancashire

Salford: roughly Greater Manchester

West Derby: all of west Lancashire to the Mersey, including the parishes of Sefton, Halsall, Ormskirk, Aughton, Warrington, Prescott, Liverpool, and Wigan.

Meanwhile, in Heysham a small village survived, isolated from the main currents of history, its people fishing, harvesting mullosks in the shallows, and tilling meagre farms. Its one unique feature was a large stone chapel on the promontory of Heysham Head.

Note that in the map above Heysham is spelled as Heseham [/hese/=brushland + /ham/=small town]; see also the Heyshams of Yorkshire page for the use of this spelling as a surname.

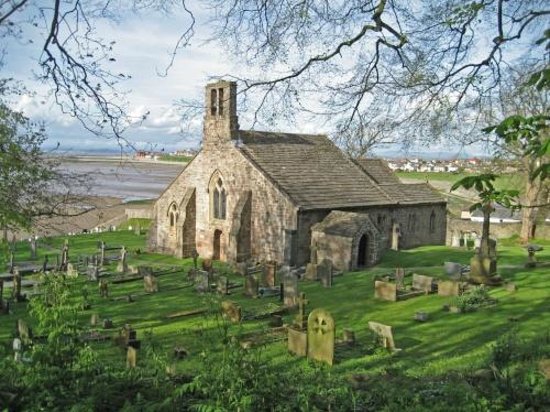

St. Patrick's Church, Heysham This Saxon church may have been built as early as the late 6th century or as late as the mid-8th (575-750 AD). Local folklore claims that it was built by St. Patrick himself, who had been shipwrecked on the coast, but since he died around 490 AD, that seems unlikely. The building is notable for its size, prominent, yet remote location overlooking Morecombe Bay, and use of stone in its construction. No other churches in the region survive from this period, most likely because they were made of timber. The use of stone was a considerable expense and may indicate the importance of the facility. The chapel may have served a monastic community, which would account for all of these factors.

This Saxon church may have been built as early as the late 6th century or as late as the mid-8th (575-750 AD). Local folklore claims that it was built by St. Patrick himself, who had been shipwrecked on the coast, but since he died around 490 AD, that seems unlikely. The building is notable for its size, prominent, yet remote location overlooking Morecombe Bay, and use of stone in its construction. No other churches in the region survive from this period, most likely because they were made of timber. The use of stone was a considerable expense and may indicate the importance of the facility. The chapel may have served a monastic community, which would account for all of these factors.

An excavation in April 1993 uncovered more than 1,200 artefacts which showed that the site had been occupied for almost 12,000 years ago. See also Cumbrian Churches.

| Historical Timeline: The Vikings, 866 - 994 AD

The Viking expansion was kept in check only by the actions of King Alfred "the Great" of Wessex. He defeated their army in 871 and again in 878, keeping the south of England free.

The Danes, however, had become acknowledged masters of the north, the region remembered to history as the Danelaw, the region where Danish law held sway. "Yorkshire, particularly the East Riding, was subjected to very heavy Scandinavian settlement which may partly account for the paucity of Celtic names" - from "British Survival in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria" by M.L. Faull in "Studies in Celtic survival," British Archaeological Report The situation was fluid, however. In 927 Athelstan, King of Wessex, decisively defeated a coalition of Irish, Norse, Scots and Northumbrians, and in 954 his brother and successor, Edmund, defeated Eric Bloodaxe, driving the Vikings out of York. |

At least three ancient remains from Sweden dated to the Viking era have been tested as Y-DNA G2a. One could only be tested to G2a, but sample VK39 from Skara-Varnhem [western Sweden], 10th to 12th century AD, was CTS11352/Z759 (G2a2b2a1a1b1a) [a grandchild of L497] and sample VK479 from Gotland-Kopparsvik, 900-1050 AD, was S2808/S23438 (G2a2b2a1a1b1a1a2a1a) [a grandchild of the downstream CTS4803].

| Historical Timeline: Kings of Wessex & Saxon England, 891-1016, 1042-1066.

Viking raiders reached Wessex in the last years of Egbert's reign. Kings of WessexEgbert 802-839Edward's son completed the reconquest of England. Kings of England Athelstan 924-939Ethelred's reign was ended by the Danish Canute. Ethelred's wife was Emma, the daughter of the Duke of Normandy. Their son was, Edward the Confessor 1042-1066 After Canute's conquest Wessex was reduced to an earldom, but in the aftermath of William's conquest all the English earldoms were dissolved and Wessex was divided amongst William's followers. |

In the 9th century St. Patrick's church in Hessam was destroyed by the Vikings, most probably Norwegians coming out of their settlements in Ireland. In general, the Norwegians raided from the west and the Danes from the east. The Church was possibly Celtic in origin. Only a single wall and a finely carved door remain.

In the early 900's the Irish succeeded in ejecting the Vikings from their colony in Dublin. These Irish-Norwegians then took to their boats and invaded the western shores of Lancashire, settling in Cumbria, the Ribble valley where there was already a substantial colony of Danes and Norwegians, and in the Mersey estuary. In order to concentrate their resources in the war against the Danish invaders to the northeast, English rulers came to an accommodation with these Norwegian invaders allowing a peaceful settlement to go forward. Viking remains and implements have been found in Hessam indicating active settlement occurred in the village during this period.

The shattered church of St. Patrick's was replaced by the present St. Peter's church, below. In 1080 it was recorded that the location was the site of an old Saxon church. Some of the fabric of that church remains in the present church. The chancel, the area around the altar, was built around 1340-50 and the south aisle was added in the 15th century. The north aisle was added in 1864. At that time an Anglo-Saxon doorway was moved and rebuilt in the churchyard, and two galleries which had served as private pews with their own entrances were taken down. This is one of the oldest churches in England and is still in use. See TripAdvisor Heysham for more photographs of the church and surronding area.

Historical Timeline: The Danish Kings, 994-1042.

Canute 1016-1040 Though defeated, the Vikings, both Danes and Norwegians, had not given up on their goal of kingship in England. By the end of the 10th century Viking raids had resumed. Afraid of being caught between an invading army and Viking settlers from previous invasions whose allegiance was in question, King Ethelred "the Unready" ordered the killing of all the Norwegians and Danes in his territory. This action caused these previously quiescent settlers to revolt, resulting in the conquest of the country by Denmark under Sven "Forkbeard" and his son, Canute. Ethelred's son, Edward, fled the county and settled at the Ducal court in Normandy, who were his mother's family. By the way, King Ethelred's nickname "the Unready" was wrongly translated from the original Saxon Redeless that actually meant "Lacking good advice." Rede was an Anglo-Saxon word for counsel. The King would have been much better advised to leave his Nordic neighbors alone. Canute ruled a vast northern empire, including England, Denmark, Norway, and parts of Sweden. He was also the overlord of Pomerania and Schleswig in modern-day Germany. Hardicanute 1040-1042The son of Canute and Emma, who was the daughter of the Duke of Normandy. She had been the wife of Ethelred and was the mother of Edward the Confessor, then living in Normandy. Harold HarefootThe son of Canute and a lady of Mercia, he also contested the throne of England, but was defeated by Harold at the Battle of Stamford bridge, just days before the Battle of Hastings. |

In 1013, as the Danish armies of Sven overwhelmed England, Uhtred, the Earl of Northumbria, son of Earl Waltheof of Bernicia, foreswore his allegiance to King Ethelred and submitted to the conquering Danes. Sven died soon after the conquest in 1014 and was succeeded by his son, Canute, as King of both England and, later, Denmark. Canute did not trust the new Earl of Northumbria, Eadwulf II, the son of Uhtred, and had him murdered in an ambush in 1041.

Canute is most famous today as the ruler that, told by his courtiers that he was all-powerful, showed his limitations by trying, and failing, to hold back the tide.

The earldom was then given to Siward, a Danish warrior who had come to England with Canute. Siward was a good ruler who brought stability to the region, if only for a little while, and was kindly remembered by the ceorls. To seal his rule, he married Aefled, the daughter of the old Saxon Earl of Northumbria. After the restoration of the house of Wessex Siward supported King Edward in his quarrels with the powerful Saxon Earl Godwine. In 1054 Siward invaded Scotland and routed King Macbeth in battle. Shakespeare introduced Siward in his famous play. Earl Siward then died in 1055. Because his son, Waltheof, was too young for such an important post in the northern marches, he was only eleven, the earldom was given to Tostig Godwinson, son of Earl Godwine who was gathering all power to himself and his many sons.

Danes were a mix of haplogrops I1 and R1b, with a smattering of R1a. .

Historical Timeline: Last of the English Kings, 1042-1066.

Edward "the Confessor" 1042-1066 Canute's son, Hardicanute, was unable to hold the throne after his father's death and the Saxon's once again reasserted their rule under King Edward "the Confessor" in 1042. Edward died childless in 1066. Harold Godwinsson 1066The son of Godwin, the powerful Earl of Wessex and closest advisor of Kind Edward. Harold was elected by the Witan upon Edward's death. Defeated and killed by William at the Battle of Hastings. |

During the final years of Saxon rule, in the last ten years of King Edward "the Confessor," and in the short reign of Harold, the district around the village of Hessam was owned by Tostig who ruled the Lancashire portion of his domain from his castle at Halton. Halton is just up the Lune river from present day Lancaster. Tostig was the third son of Earl Godwine of Wessex, the most powerful of the Saxon lords, and brother to Harold, later to be King. In 1065 the Northumbrians revolted against Tostig's severe rule and chose Morcar, brother of Earl Edwin of Mercia, to be their Earl. When Morcar and Edwin then turned their armies south in a bid to seize the throne, Harold, advising the king, negotiated a settlement giving Northumbria to Morcar and dispossessing his brother, who fled to Flanders. Tostig never forgave Harold. The next year Tostig raided the English coast, then joined forces with the Norwegian King Harold III "Hardrada," invading the north and defeating Morcar. Earl Tostig was subsequently killed at the battle of Stamford Bridge in which the Norwegian invaders were defeated by the new king, Harold, on the eve of the Battle of Hastings.

To get a feel for the mix of nationalities and cultures existant in the region around Hessam at this time, as recorded soon after in the Domesday book, the names of the men included Alflaed, Alfred, Alwine, Arnketil, Biarni, Claman, Dolgfinnr, Egbrand, Everard, Flotmann, Gamal, Gamal Barn, Gluniairnn, Gospatric, Gunnar, Hrafnsvartr, Ketil, Leysingr, Orm, Ramkel, Rawn, Suneman, Thor, Thorbiorn, Thorbrandr, Thorfinnr, Thorgrim, Thorkil, Toli, Ulf, Ulfkil, William, William de Percy, and Wulfric.