|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

The Hissem name is an extremely uncommon one, a fact that has made assembling this descent so much easier than if our name had been Smith. I can be fairly certain that if I find a reference to a person named Hissem, or its common variants, Hissam, Hissom, Hissim, or even Hessom, that I'll be able to find a link back to my own family. Our name is not uncommon simply as a surname, but as a word as well. That is, in contrast, while 'Racoon' is a pretty uncommon surname too [yes, I'm thinking of Rocky Racoon who walked into a room . . .], it is a fairly common word. The unique nature of Hissem as name and word has made internet searches both easy and productive.

The Hissem name is an extremely uncommon one, a fact that has made assembling this descent so much easier than if our name had been Smith. I can be fairly certain that if I find a reference to a person named Hissem, or its common variants, Hissam, Hissom, Hissim, or even Hessom, that I'll be able to find a link back to my own family. Our name is not uncommon simply as a surname, but as a word as well. That is, in contrast, while 'Racoon' is a pretty uncommon surname too [yes, I'm thinking of Rocky Racoon who walked into a room . . .], it is a fairly common word. The unique nature of Hissem as name and word has made internet searches both easy and productive.

In the story I will tell, I trace the origin of the name Hissem back to a small village, called Hessam in the Domesday Book of 1086 AD, but now known as Heysham, in the county of Lancashire, in northwestern England. The village, though settled for millenia, got its name after the Anglo-Saxon conquest of the region in the 7th century AD. The use of the village's name as a surname, for example "John of Hessam" or, in the Norman-French of the day, "John de Hessam," dates to the 13th century when the widespread use of such descriptors first arose. It was at that time, I think, that members of my family lived in the region and earned the name.

This means that other members of our family, those who may have shared a common ancestor just a generation or so before this "name-giving" period, exist who do not share our surname. They may have earned an occupational surname, like Fletcher (one who adds feathers to an arrow), lived in a nearby village and were called by its name, like Middleton, Overton or Heaton, or were named after their father, like Johnson or Robertson. While I'll get into DNA testing later, let me note that a Brian Fletcher is closely related to us, sharing a common ancestor between 16 and 20 generations ago with a 98 to 99% certainty. This takes us back to the 13th century. In the 17th century members of the Heysham (Hyshem) and Fletcher families lived in Highfield, just northeast of Lancaster.

My theory about the origin of our surname is not based just on the number of common letters in the names Hissem and Hessam, but in the way the spelling of both the village's name and our surname varied over time. In colonial America our name was spelled as Heesom, Hesom, Heesham, Hysem, Hysham and Heysham, all variants applied to the village in England in the same period. I figure this can't all be coincidence. We'll discuss other evidence for my origin theory as this story develops.

By the way, some years ago, when I was first putting this site together, I communicated with the village of Heysham's Historical Society; their online store had a couple of books for sale that looked interesting. They immediately recognized the correspondence of the town's name and my surname.

I suppose it is appropriate to stop here and list all of the surname variants I've identified in both England and America.

Hissam, Hissem, Hissim, Hissom, Hissum, Hissym, Hyssom,The last are dropped-H versions of the name; it's a northern thing. Anyroad, I'm right 'appy w'thot.

Hisam, Hisem, Hisom, Hisum,

Hessam, Hessom, Hessem, Hessum,

Hesam, Hesame, Hesom, Hesome, Hesum, Hesaym, Hasom,

Heesam, Heesame, Heesom, Heesome, Heisam,

Hesham, Heshame, Heseham, Hessham,

Heesham, Heeshame, Heisham, Heishame, Hesham, Heisam, Heisom, Heisum, Hisham, Hishame,

Heysham, Heyshame, Heysam, Heysame,

Hysham, Hyshame, Hyseham, Hyesham, Hyesome, Hysam, Hysame,

Heghsham, Heighsam, Heighsham, Highsham, Highshame, Highsam, Highsame,

Haysham, Hayshame, Haysam, Haysame, Hashame,

Hoysham, Hoysam, Hoseham,

Haysom, Haysome, Heysom, Heysome, Hysom,

Easam, Easame, Easom, Easome, Esum

How can there have been so many variations on one, not very common, surname? It was simply that spelling was not considered to be especially important in this early era. If the combination of letters approximated the spoken word or name, it was considered adequate for the purpose. In Bill Bryson's "Life of Shakespeare" he reflects on this attitude.

"Spelling was luxuriantly variable, too. You could write "St Paul's" or "St Powles" and no one seemed to notice or care. Gracechurch Street was sometimes "Gracious Steet," sometimes "Grass Street" . . . Christopher Marlowe signed himself "Cristofer Marley" in his one surviving autograph and was registered at Cambridge as "Christopher Marlen." Elsewhere he is recorded as "Morley" and "Merlin," among others. In like manner the impresario Philip Henslowe indifferently wrote "Henslowe" or "Hensely" when signing his name, and others made it Hinshley, Hinchlow, Hensclow, Hynchlowes, Inclow, Hinchloe, and a half dozen more. More than eighty spellings of Shakespeare's name have been recorded, from "Shappere" to "Shaxbred.""In defense of early historical spelling, it is important to remember that there were no dictionaries, gazetteers, or directories yet to tell someone how to spell a word or the name of a person or place. People did the best they could.

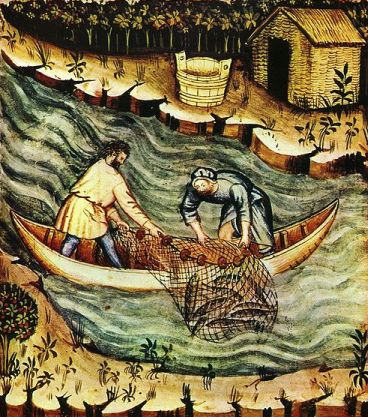

Lancashire, in which Heysham lay, was not a rich county. In fact, before the industrial period, it was one of the poorest and least densely populated in the country. Its coasts are marshy, gradually being replaced by forest as you head east into the Pennine Mountains, which rise above 2000 feet. There are wide moorlands or heaths, extensive bogs, which yield only turf for fuel and are dangerous to travel across, and some fertile land for agricultural purposes. Grazing, however, was more common than farming. Fish, taken both in the rivers and the sea, and mussels, harvested from the extensive shoals, were central to the population's diet and explains why most of the early villages were within 20 miles of the sea. The area was not heavily settled until recent times, when coal mining and textile manufacturing became the chief industries.

Lancashire, in which Heysham lay, was not a rich county. In fact, before the industrial period, it was one of the poorest and least densely populated in the country. Its coasts are marshy, gradually being replaced by forest as you head east into the Pennine Mountains, which rise above 2000 feet. There are wide moorlands or heaths, extensive bogs, which yield only turf for fuel and are dangerous to travel across, and some fertile land for agricultural purposes. Grazing, however, was more common than farming. Fish, taken both in the rivers and the sea, and mussels, harvested from the extensive shoals, were central to the population's diet and explains why most of the early villages were within 20 miles of the sea. The area was not heavily settled until recent times, when coal mining and textile manufacturing became the chief industries.

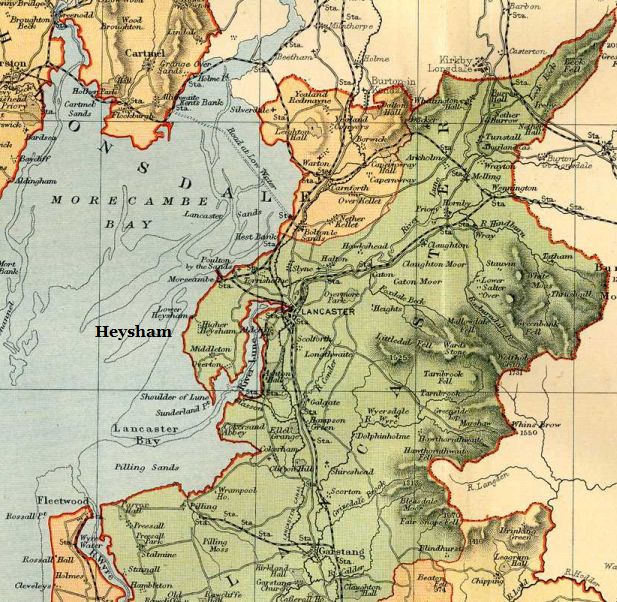

The area, in the map to the right, is bounded on the west by Morecambe Bay and the Irish Sea; in the east by the Pennine mountains at the border with Yorkshire; in the south, at the border with Cheshire county, by the river Mersey, upon which the modern city of Liverpool is located; and in the north, at the border of the old Westmorland county, now combined with Cumberland into the new county of Cumbria, near the Lakes district. From south to north, the rivers Ribble, Wyre and Lune cross through the county; the Ribble, at the town of Preston; the Wyre, at Fleetwood; and the Lune, passing through Lancaster and behind the village of Heysham.

Below is a photograph of the Lune river valley, just east of Lancaster.

The Village of Heysham

The Village of Heysham

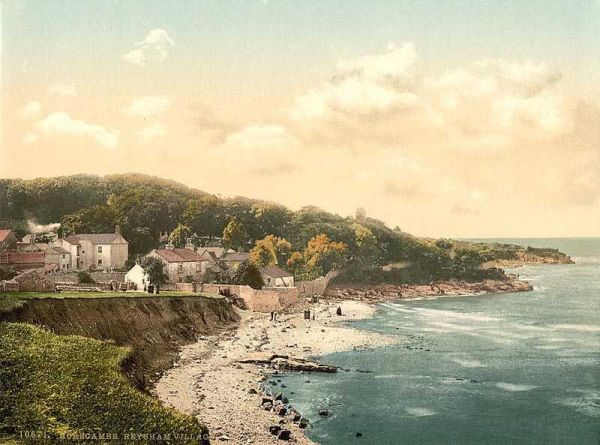

Heysham, pictured to the right, was until modern times a very small and relatively poor place. The original settlement was located on the top of a small rocky prominence called Heysham Head, adjoining the sea. Later, the area behind the promontory was settled in what became known as Higher Heysham and, to the north, or left in the photograph, a seaside settlement became known as Lower Heysham, shown also in the painting below, with Heysham Head in the background. What you can see in the modern photo is the Heysham church, built circa 1000 AD, and its graveyard, behind a sea wall.

The land to the north, east and south of Heysham falls away to a low-lying moss, or 'spongy flat,' dangerous to cross at high-tide, and isolating the village from the surronding countryside. Peat bogs, reedbeds, salt marsh, Gorse and scrub predominate.

". . . Heysham, an outlying parish on the River Lune, quite hard to reach from Lancaster because of the mosses in between . . . " - from "John Marsden's Will: The Hornby Castle Dispute, 1780-1840" by Emmeline GarnettIn the dangerous times of the Dark Ages and the Early Medieval, this was an easy-to-defend location. The village's seaside location had a downside, all of its wells were brackish.

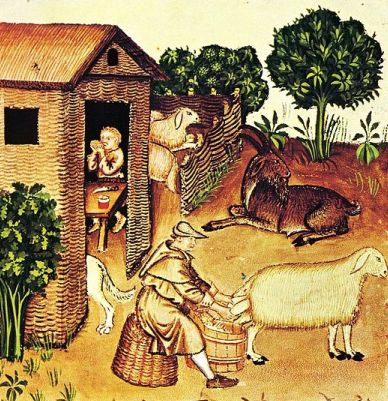

The people of Heysham, lying on Morecombe Bay as they did, would have been mainly fishermen, using small shallow-draft boats to net fish in the bay and harvesting mollusks in the shallows of the numerous sand banks. There was some farming of wheat, oats and barley, but with the poor soil in the area pasturing animals, such as sheep and goats, was more common. In the Medieval the village had just four farmlands, each capable, in theory, of supporting one family for a year. Hunting in the local forests for large game was generally forbidden, those being reserved for the aristocracy, but small game, such as rabbits and birds that would overwise maraud the fields, would be trapped.

Heysham had a population in the early medieval, and especially after the devastation of the Bubonic Plague in the late 14th century, that probably did not rise above a couple hundred. The reason the Hissem name is so uncommon then, even with the many variants I will identify, is because its place of origin was so very small. Even if multiple families adopted the village as a surname, the starting population was still quite limited.

Let's look at this for a moment. A population of 200 means about 50 families, or less. All, during the coming century, would need surnames to support the work of the growing government bureaucracy. Many would be named for their fathers, i.e. Johnson, Thompson, or Williamson; others would be named for their occupations, i.e. Baker, Carpenter, or Miller; others would get names based on their nicknames, i.e., Blakely, Dickens, or Moore; some would get names from where they lived, i.e. Marsh, Banks, or Forest; leaving just a few to be named after their village of origin, i.e. Heysham or Hessam.

See Evolution of Names for a more in depth analysis.

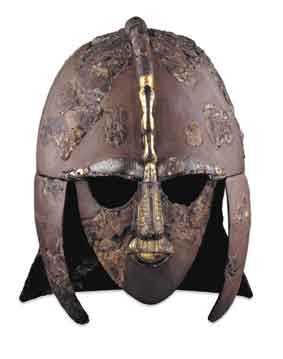

In the 7th century AD, when the village was named, the Anglo-Saxons ruled the region. Their language was Englisc, or Lingua Saxonica according to the Latin authors, which today we call Old English. It was a branch of the West Germanic language family known as Low German. This was the precursor to not only modern English, but Dutch, Flemish, French and modern Low German. In England it was broken into several dialects, Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish and West Saxon. It is unintelligible to modern English speakers. Below are the opening lines of the Beowulf saga, the most famous work in Old English. It was written down around the year 1000. Hear this at Beowulf Reading in Old English.wmv.

HWaeT, we Gardena in geardagum,Old English is generally considered to have been the language of common usage from the 5th to the mid-12th century. During that period it picked up elements from the native Celtic, Danish and Norwegian dialects of Old Norse brought by invading Vikings, and Latin phrases from priests as the pagan Germans were Christianized.

peodcyninga prym gefrunon,

hu oa aepelingas ellen fremedon!

oft Scyld Scefing sceapena preatum,

monegum maegpum meodosetla ofteah,

[translation]

LO, praise of the prowess of people-kings

of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped,

we have heard, and what honor the athelings won!

Oft Scyld the Scefing from squadroned foes,

from many a tribe, the mead-bench tore,

There are at least two theories to the origin of the village of Heysham's name. In Old English,

There are at least two theories to the origin of the village of Heysham's name. In Old English,

"haes [hese, haese, hese," or "hyse"] meant "of woodland country, land with bushes and brushwood . . . The cognate Germ. hees (OHG he(i)si) is applied to similar country." - from "Survey of English Place-Names."See also "An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary" by Joseph Bosworth and Thomas Northcote Toller. In this sense "haes" may refer to uncleared land; that not already under cultivation.

"Heysham (ancient parish) PNLancs p. 178The "Victoria County History: A History of the County of Lancaster," 1914, also has the following spellings of the villages name,

Hessam 1086, Hesseim, Heseym 1094, Hesheim 1190-99, Hissein 1200+, Esham 1208+, Heysom 1701+

OE haes 'brushwood, swine pastures', with ham. Forms with -(h)eim,

-eym, show Scand influence. ..." - from "Journal" by English Place Names Society

"Hessam, Dom. Bk.; Hessein, 1194; Hessem, Hissein, 1200; Hesham, 1208 and common; Heshem, 1209; Hesaim, 1212; Hessam, 1246; Heesham, 1291; Hegsham, 1292; Hesam, 1297."Another reference says similarly,

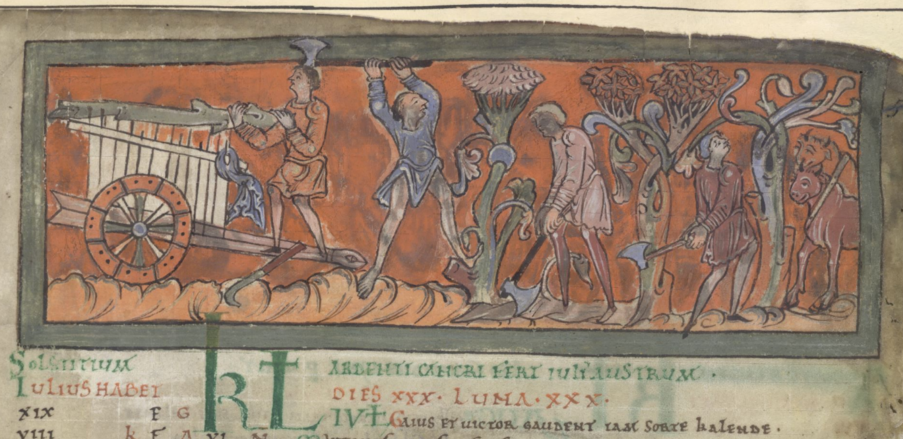

HEYSHAM PAR.Note that the English name Hayes is also derived from the Anglo-Saxon haes, meaning brushwood; also as underwood, undergrowth. Hese and hesa were 12th century spellings of the name. The village's name was rendered as Heseham in Speed's map of Lancashire in the 17th century. The similar 'hay' is an old English word for a hedge or defensive perimeter; think of the Tolkien's High Hay which was a defensive hedge around the village of Buckland. A thick hedge might not keep out determined invaders, but it would keep animals in and discourage trespass. So was Heysham perhaps a hamlet surronded by a hedge? Below peasants cut the brushwood.

A district on the sea, W. of Lancaster, S. of Morecambe.

Heysham, Higher and Lower (hamlets) : Hessam DB [Domesday Book], Hesseim, Heseym 1094 Ch, Hesheim 1180-99 Ch (orig.), Hesam 1212-17 RB, 1297 LI, etc., Hessein 1194 LPR, Hessem 1201 LPR, Hesham c 1190 Ch, 1208 LF, 1246 LAR, 1332 LS, etc., Hesaim 1212 LI, Heesam 1246 IPM, de Heshaym 1259 IPM, Hesaym 1272-5 FC II. (orig.) ; Heghsham 1323 LI, Hyseham 1557 LF ; magna, parva Hesham LC 298, Hesaym Superiori 1285-8 FC II., Nethir-hessam 1297 LI ; now [hrjam], but Ellis, p. 626, gives the form [ :fisBm].

The second el. of the name seems to be O.E. ham rather than hamm ; it is often Scandinavianized to -haym, etc. The first is no doubt O.E. hces. This word corresponds to a L.G. word very common in place-names (as Hees, Haiss, etc.) and apparently still in living use in the form hees or hese ; the meaning seems to be "brushwood, underwood" (cf. Forstemann, Namenbuch 1196ff., Nomina"

- from "The Place-Names of Lancashire"

"Ham", or -am, was also from the Anglo-Saxon and referred to a home or manor. Hamleas meant homeless. It could describe something as small as the few buildings of a single family homestead [hamstede], or as large as a village. The word hamlet survives, meaning a small village. The suffix was also sometimes rendered as "haym" or "heim", perhaps reflecting Norwegian or Danish influences. Ham is a very common termination to town names in England, examples including Notting-ham, as well as South-ham-(p)ton, which meant "south-home-town;" "ton", or -tun, being from the Anglo-Saxon for a town, usually one enclosed by a wall or hedge.

So Haes-ham, or Hees-am, would mean 'homestead in the woods,' and one probably not large enough to be defended by an enclosure. There is indeed a wood on the top of Heysham Head, see above.

More often, however, popular genealogies or town histories claim that Hessam, or Hess-ham, meant the village of the family or clan of Hess. Another source goes as far as to claim that Hessa, a roving Saxon [sic] chieftain, took possession of the village and it was named for him. This is based on the perception that the -ham suffix most often referred to the house or homestead of the head of a family, the -ham being combined with the family patronymic. The Germanic patronymic combined the head of the family's name with the termination ing, thus Beorn-ing-ham was the homestead of the sons of Beorn, today's Birmingham.

So, Hessa may have been an Anglian warrior, a vassal of King Oswald, who, as a reward for his service, was given land west of the Lune river and the village was named for him. This would have occurred not long after South Rheged was annexed, circa 615.

The village was called Hessam in the Doomesday Book of 1094, but the spelling of the name evolved rapidly over the years. This was probably because there was little literacy, no rules about spelling, nor any authoritative dictionaries during this period. It was known as Heseym in a document recorded in 1094, as Hesham in 1190, Hessein in 1194, Hessem & Hissein in 1200, Hesaim in 1202, Hesham in 1208, Heshem in 1209, Hesaim in 1212, Heesam in 1246, Heesham in 1291, Hegsham in 1292, Hesam in 1297, Heghsham in 1323, Hyseham in 1557, and variously as magna parva Hesham, Hesaym Superiori, and Nethir-hessam.

By the second half of the 17th century, when the first emigre of our family left for America, the village was known variously as Hysham, Heysham, Heysam, Heisam, Heisham, Heesham, or Heesom. The latter two variants are how the first of our family spelled his name in America. Heysham only became the standard in England after 1700 when a prominent London branch of the family, read "rich," adopted the spelling; previously they had spelled it as Heisham or Heesom. By the way, that prominent family died out in the 19th century so we don't inherit. See the Merchants of Lancaster page for more information. To see how our name evolved even further in America, see the John Heesom page.

The local pronunciation of the village name in Lancashire today is /hee-sham/, although I met a northerner who insisted the only correct pronounciation was /hay-sham/.

"Heysham, as parish registers show, was the normal spelling even in Stout's day [c1700], although Heesham, suggesting a common pronunciation, appears in the burial register of that parish for 1710. Another form, according to a local witness, was pronounced Hees-(h)am (nineteenth century)." - from "The Autobiography of William Stout of Lancaster" by John Duncan MarshallHowever, some early spellings, like Hesam or Hessam, seem to infer that originally the first syllable may have been pronounced with the short e sound of 'eh,' as /heh-sam/. Actually I think the learned way to present this is /?:/ is 'eh' and /i:/ is 'ee,' but that looks strange to me so I'll continue to use my own idiosyncratic method of phonetics.

I think an explanation for this difference may lie in an event known as the Great Vowel Shift. This change in pronunciation occurred for unknown reasons in England between the 14th and 16th centuries. Its influence was greatest in the southeast, especially in London, and gradually diminished as it moved north. I suspect that the pronunciation of the village's name changed under this influence and, just as the London branch of the family imposed their unique spelling of the name, they also imposed their London pronunciation.

| The Great Vowel Shift

This shift comprised changes in the pronunciation of the English language that took place between 1350 and 1600, roughly from the period of Chaucer to that of Shakespeare. The change began in the south and worked its way north, becoming weaker as it did so. The shift occurred mainly in the pronunciation of the "long" stressed vowels. For example, in Chaucer's day food, good and blood all rhymed, having the long /o/ sound of goad; the double 'o' was the clue to the pronunciation. Spelling was not altered to match the change in pronounciation, making English notoriously difficult to spell by rule. Some simplified examples, a = the ah sound became ay (ex. "make") |

So /heh-sam/ may have become /hee-sham/ under the influence of southern pronunciation patterns. However, I don't think that the pronunciation of the family name evolved uniformly. Those having the least contact with society or government would have held on to the old pronunciation. The latter case is most clearly seen in the north of England.

My personal theory of the evolution of pronunciation is that it will tend to drift if it lacks an anchor of some sort. This anchor is something like the gravitational pull of a large planet. So in this instance, a member of our family that lived in or near the village of Heysham would tend to spell and pronounce their name just like that of the village. If, however, they moved far enough away to escape the influence of the village, and if the move occurred before the vowel shift, then their name's pronunciation would be unlikely to be affected by the new fangled pronunciation of the village's name. As we'll see in later pages, the Heysham family of London adopted the /hee-sham/ pronunciation of the south and their fame (they were Lancashire MP's) resulted in the imposition of this pronunciation on the village.

The Heysham family of New York and Pennsylvania, members of our family who changed the spelling of their surname in the middle of the 19th century, pronounce their name as /hesh-am/, with a short-e of 'eh.' The Heesom family of Warrington, in south Lancashire, pronounce the name as /hi-som/, with the short-i sound of hit. The Heesom family of Hull, East Yorkshire, pronounce the name as /hess-om/, with the short-e sound of 'eh.' Note that one branch of our family in America spells their name as Hessom. In all cases the stress is on the first syllable of the surname.

I also believe that pronunciation is primary; the spelling of a name or word will change with changes in its pronunciation, unless there is, again, an anchor to hold its spelling in place. My family pronounces the name as /hiss-em/ and, lacking an anchor by our long separation from the village of Heysham or from our cousins, the Heesom family of Hull, evolved the spelling to Hissem, moving through Heesom-Hesom-Hissom-Hissam-Hissem. The spelling of the name went back to Heysham/Hysham briefly, around the time of the Revolutionary War, but I believe that was because a patriot in Philadelphia, Captain William Heysham, became briefly famous.

Reference the above, why didn't spelling of the English language change to match the new pronunciations of the vowel shift? Apparently this was due to the invention of the printing press and the widespread availability of books beginning in the 1400's. This froze spelling as it existed at the beginning of the Great Vowel Shift. It also began the standardization of spelling which climaxed with the publication of Samuel Johnson's dictionary in the 18th century.